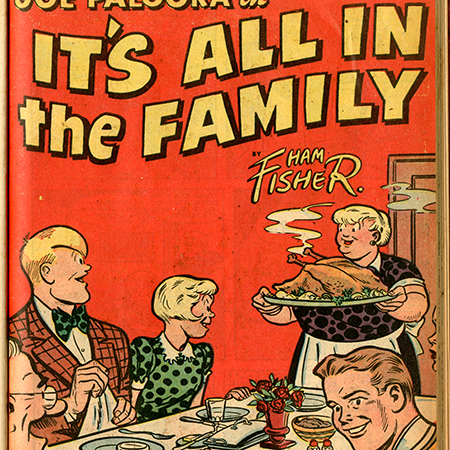

“It’s All in the Family,” in

Citizenship Booklet

c1951

The male body is inextricably associated with notions of masculinity and anatomically based, binaristic gender constructions of the era. The body, its physical strength, and its sexual virility, were essential markings for a man’s masculinity. Connell wrote, “True masculinity is almost always thought to proceed from men’s bodies — to be inherent in a male body or to express something about a male body.[^] Non-masculine body types were often associated with weakness — physically, intellectually, and morally. A man’s physical masculinity was a status symbol, one that many politicians utilized in their campaigns, publicizing their achievements as warriors and athletes, and downplaying any physical shortcomings.[^] One’s bodily masculinity could be used both as a way to assuage doubts or criticism of a man as well as a way to attain an elevated social status.

The perfection of bodily masculinity was a central component in military training, as well as in the military’s public perception. Belkin wrote, ”…constructions of the soldier’s toughness, masculinity, dominance, heterosexuality, and stoicism can conjure images of military strength, state legitimacy, and imperial righteousness, while depictions of the soldier’s flaws can implicate notions of military weakness and state and imperial illegitimacy.”[^] Belkin argues that this gives reason for the military to insure that normative masculinity of the solider, military, and state were all aligned. These constructions and this imagery would have direct repercussions on American manhood, especially for the men in the military, who were the subjects of the constructed manhood. Within American society and American masculinity, Belkin argued, ”…the ubiquitous characterization of American military masculinity as an ideal that marks not just being a man, but a real man, and the association of authenticity and legibility with warrior masculinity in US military culture” resulted from military masculinity’s insistence of its own flawlessness.[^] Echoing Regina G. Kunzel and Michel Foucault, Belkin argued that this insistence proved the constructionism of military masculinity, and the power wielded in the mask of normativity.[^] This imagery and the linkage of proper manhood with military masculinity raised the status of soldiers and veterans’ manhood and assuaged any doubts about them.

In military documents, physical masculinity was used as a signifier for success and triumph, and a lack of physical masculinity was used as a marker for failure and impotence. Federal productions, in combination with similar materials in popular culture and the intrusive Selective Service examinations, reinforced the notion that American soldiers were ultra masculine men in a very specific vein — white, tall, clean-cut, strong jaw line and facial features, and a strong frame.

The draft brought about a national discourse on the physical well-being of its citizens, especially its young men. In addition to young male bodies representing the nation’s strength, courage, and aggressiveness, Christina Jarvis argued that during WWII, “American male bodies were physically examined, classified, categorized, disciplined, clothed in particular uniforms, sexualized via venereal disease screenings, and subject to numerous other processes by the military and other institutions.”[^] This process, applied to tens of millions of men over the course of the Selective Service draft, brought about a national discourse on the health and bodies of the nation’s young men. During WWII, when the draft was at its peak, “Newspaper stories about the Selective Service system were filled with the terms, and ‘one’s draft status became the topic of daily conversation and radio comedians’ jokes.’”[^] While service in the military could provide others with basic assumptions of a man’s physical capabilities, sports provided another avenue to display one’s masculinity in a way that was culturally heralded and highly visible. Historian Anthony Rotundo argued that, beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, competitive sports took on a ”…new meaning and heightened importance for Northern US men.”[^] Goldstein endorsed Rotundo’s view, and added, “Physical culture shifted focus from strengthening the body to competition, and sports played an important role in the emergence of the new ideals of manhood at the turn of the century.”[^]

Robert Dean found sports to be one of the primary arenas where Cold War-era elites earned social status and prestige. “The ‘big men’ of the schools were often the athletic stars. The agon of athletic competition was metaphorically linked to the experience of war, with analogous opportunities to achieve a kind of immortality, a ‘homosocial rebirth.’”[^] Dean stressed the importance of this status and social ascendancy, adding, “Athletic accomplishment was associated with ‘leadership’ by the masters; positions of authority over other boys often went to those who excelled at sports.”[^]

Through athletic success, both in the past and through ongoing competition, markers for manhood such as physical strength, aggressiveness, and courage could be produced, displayed, communicated, and compared with other men. Most military installments outside of combat zones participated in competitive sports, and often had intramural leagues and teams that competed against other military installments and local teams. These events were often well-attended and well-covered by local media sources, and thus publicized men for their athletic ability and made them well-known around the military installment or community. Individual men were able to establish reputations for their physical well-being and their athletic abilities. These same kinds of skills and abilities, and the value and appreciation assigned to them, were often expressed through comics to portray men in the military as being superior athletes and physical specimens. These pieces insisted upon a specific type of physical masculinity — athleticism — that was culturally valued, and allowed men to achieve higher social standing through performance. In these pieces, the playing field was as an important social space where men gained recognition, status, and an identity woven into their achievements.

The power of athletic ability in gaining social status is well-illustrated in the comic It’s All in the Family. The story stars Joe Palooka, a well-known syndicated character, who is a heavyweight prizefighter. The neighbors, Henry and Mrs. Harris, directly acknowledge his ‘bigwheel’ status and the weight it carried when they are first struggling to start their car. When Mrs. Harris suggests Henry ask the Palookas for help, Henry responds with, “Listen…I’ve never asked help from that kind of people before..”[^] When asked what he means, he replies, “His son is the heavyweight champion of the world — so they probably think they are real stuff and we’re nobody!”[^] Even though the Palookas thoroughly disprove Henry’s assumptions, he is taking Joe’s pedigree as an athlete and the notoriety he has gained to assume that the Paloookas are of a higher social class and would not give any mind to someone of his class. It also demonstrates that, although he has never met any of them, he has heard of Joe’s talents and accomplishments, and that his reputation (at least so far as his athletic ability) precedes him.

The military gave the impression that soldiers, especially he best ones, came from the ranks of the nation’s elite athletes and best physical specimens. Athletes were typically heralded for many of the same things soldiers were — their strength, courage, and keeping their wits about them in harrowing times. Characters were often masculinized through the display of past athletic achievements, creating a bridge between the status of athletic “big wheels” and the soldier.

Athletics and male physical power were very much stressed in the material, depicting many soldiers as former athletes. The comic, “Mister Marine Corps” comes from United States Marines No 7, a compilation of news, photojournalism, and comics printed by the US Marine Corps. The central character, “Mr. Marine Corps,” is Lou Diamond, is an aging Marine whose legend precedes him. This “Marine Hall of Fame” feature seeks to bolster the mythology that surrounds him, by publishing the exaggerated and fictional reports of his exploits. Lou’s athletic ability plays a big role in this mythology. First, in a departure from the battle-centric imagery throughout the piece, an early scene shows him on a baseball field, adding, “But some claim he was fifty years old when he pitched a one-hit shutout for the Quantico Marines some time in the twenties.”[^] The conversation between Lou and a teammate encourage his prowess as a pitcher and the team’s overall success. His competitiveness, along with his masculine bravado, soon comes into play on the battlefield. Despite his age, the narration reads, “…he proved his right to the title of the greatest mortarman in the world,” and he continued to serve with honor and distinction.[^]

Through the discursive linkage between sports and the military, a close tie was drawn between the accepted physical prowess at home and the physicality of the male soldiers, and placed them in the dominant and highly regarded hegemonic social role. In addition to displaying soldiers as former athletes, athletics were shown to be a large part of military life. While the former often plays on the “Big Wheel” persona, the latter functioned as a masculine discourse. Athletic competition between men is a performance of masculinity, and creates a communication of strength and physical virility between the men. The projection of this discourse serves the same function, by showing that these men are physical specimens and work to maintain this status. A publication on life at the new US Air Force Academy, an elite institution that only sought the best and brightest, featured several pages of photographs of cadets engaged in organized athletics. The Academy also highlighted the rigorous physical training, intramural sports leagues, and competitive intercollegiate athletic program they offered.[^]