Introduction to the Military Masculinity Complex

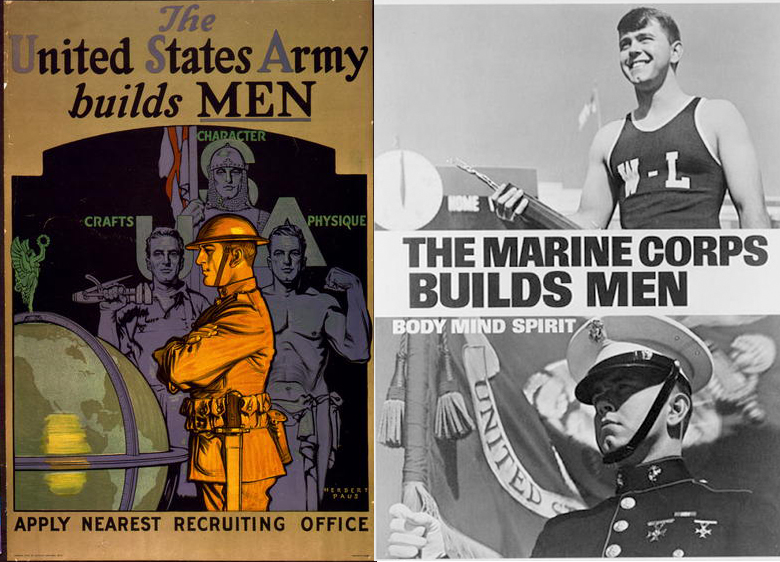

Left: Herbert Andrew Paus, “The United States Army Builds Men. Apply Nearest Recruiting Office,” 1919. Right: United States Marine Corps, “The Marine Corps Builds Men : Body, Mind, Spirit,” 1965. (US Library of Congress)

The military builds men. The linkage between manhood and military service has existed for centuries, and has been present across cultures. In the United States, military and defense propaganda have expressed this concept for more than a century. This notion is not always explicitly described, but is nearly always present as a package of imagery and narration that clues the reader in to what the federal government and the military have in mind when they say they will “build” a man. Taking a more critical view of these sorts of expressions, one can flesh out some key concepts and definitions this powerful institution held in relation to gender and its utility in propaganda.

Notions of gender - most commonly understood as masculinity and femininity - are not innate to the male or female sex, but rather are socially constructed. Gender roles and representations are highly dynamic, and their definitions are always in flux. Cultural norms and definitions change in response to social, cultural, political, and economic pressures and vary across space. Idealized masculinity holds hegemonic power over other genders, though it faces constant contestation from those who represent themselves in ways outside the mainstream. I focus on the definitions of manhood put forth by the US military and the ways in which it sought to draw power from idealized masculinity, while simultaneously reifying and elevating it.

The Great Depression brought about a sudden shock to the standards of manhood, which were largely contingent upon the economic stability of the ‘Self-Made Man,’ and his ability to provide for himself and his family.[^] The expansion of the military-industrial complex, beginning at the start of the Second World War, brought about new catalysts, avenues, and definitions for manhood in America. The war brought with it a growing economy and an immense need for soldiers, facilitating possibilities for men to fill the masculine roles of breadwinner and soldier. In her book on Western masculinity, Slow Motion: Changing Masculinities, Changing Men, Lynne Segal wrote, “In short, there were at least two opposed faces of masculinity in the fifties. There was the new family man, content with house and garden. And there was the old wartime hero, who put ‘freedom’ before family and loved ones.”[^] The former may exhibit a “softer” image of masculinity than the latter, but both fulfill cultural expectations for what roles men should fill. Throughout this project, I seek to study the discursive relationship built between ideal manhood and military service and expressed through popular media - primarily comic books and illustrated pamphlets.

While ideal gender roles and expectations of the era drew heavily upon very traditional definitions, they were also rigidly defined in an emerging nationalist ideology, often referred to as the “American Way.” The American Way is a loose set of cultural norms and meanings that emerged in the face of economic struggles and the threat of Fascism and Communism.[^] In his study of manhood and popular culture in the 1950s, James Gilbert wrote, “I believe the 1950s were unusual (though not unique) for their relentless and self-conscious preoccupation with masculinity, in part because the period followed wartime self-confidence based upon the sacrifice and heroism of ordinary men.”[^] Although racial and class barriers to idyllic manhood still existed even after military service, the military service provided a broad avenue through which men could attain higher status through economic advantages and respect and admiration throughout society. According to the narrative of military service, which was broadcast through the federal government as well as popular culture, every American GI had put his country first, and had defended the nation bravely and honorably.[^] The cultural imagery put forth by the United States military, which I study in depth throughout this project, creates a “military masculinity” that is highly idealized, and promotes a similarly idyllic masculinity for men not only during service, but also in the private sphere.

Military Masculinity

Notions of masculinity were present throughout society and culture, and individuals were inundated with positive and negative examples of masculinity all the time. Though it was certainly not alone in communicating ideal masculinity, the military, with its broad reach and institutional power, had a significant, and growing, impact on the norms of the nation. The militarization of the nation had great influence in shaping the masculine ideal of the WWII and Postwar Eras in a number of ways, including through training, GI benefits, shared experiences, and the reputation men would receive from service. I focus on the latter aspect, specifically on the creation of a valorous masculine culture ascribed to American servicemen.

The perceived vital role of men in pushing forth the American way in the face of Fascist and Communist threats was not limited to active service in the military or jobs in the defense industry. For a nation becoming increasingly militarized in the face of the specter of existential threats, the strength, courage, and intelligence of the men in an all-male military was essential to keeping freedom and liberty intact. The culture created by the military encouraged the importance of these men in all of their roles in society. Men who did not serve or had returned from service were understood as heads of their families and part of the capitalist system; which was engaged in its own ideological war with the Communist world. These dual roles of nationalistic manhood — often two stages in a man’s post-adolescent life — would define men’s role in society through the immediate postwar era and into the sixties. The military’s vast production of cultural propaganda were steeped in ideals of hegemonic masculinity and helped set examples for soldiers to follow, while also broadcasting messages about soldiers to the general population.

The masculine ideal put forth in these defense materials were largely based upon very traditional, white, middle class masculinity that exuded aggression and strength, but also control and gentility. The American military was composed of men from all different races, classes, backgrounds, temperaments, and sexualities. However, imagery surrounding these men exhibited in film, advertisements, and federal productions, show a very narrow scope of men — white, middle class, well-built, straight, and cissexual. Men who did not meet this ideal - people of color, the working class, homosexuals, and disabled - were not only excluded from the imagery put forth by the government, but were also often barred from service or denied the economic benefits of their service. Their exclusion from imagery associated with American manhood and heroism denied them mainstream idyllic masculinity, as put forth by the federal government. Masculine norms were challenged and contested, particularly from those men marginalized by these policies, but the narrative put forth by the federal government was devoid of these nuances and alternative masculinities. By injecting these white, male, middle class norms into the materials, the military stood to benefit in a number of ways. Primarily, it presented an idealized and unproblematic image of the military-industrial complex that cities could be proud of and comfortable with. It hid the ugliness of war and the contradictions men often faced throughout their service, and served as a barrier to criticism of policies and actions. The nation rallied their support behind a military that was defined through media as being an ideal hegemonic male, establishing and reifying an unattainable image of masculinity. By producing media material that put forth the American soldier as a hero, these military publications also put forth ideas about what was normative, and aligned, as Aaron Belkin argued, white-male-straight-man with American-military-empire.[^] Belkin found that the military’s treatment of masculinity and heterosexuality was used as a tool to ease the ugliness of empire with ‘purified’ troops of unquestionable morality.[^] Secondarily, the communication of unattainable masculinity, packed in the American white, straight, well-built American soldier fueled existing power dynamics that marginalized alternative cultures that could potentially cause disruptions in a society in crisis.

Hegemonic Masculinity and the Selective Service

The Selective Service Draft placed the Department of Defense intimately inside the lives of all young men, and granted the military a place of power, where they could determine which men would be accepted or rejected. This judgment, based in part upon a man’s physical body and perceived sexuality, often subjected men to either benefits and respect or ridicule and doubts about his physical, psychological, or sexual well-being. Although the DoD was being pragmatic (even if they were greatly misled by their own ideas about sexuality and physical well-being), their decisions would have a major impact on the lives of the men they inspected and graded.

The honor of service and GI benefits, along with the conceptions of masculinity and the economic boosts that accompanied it, were not available to all men, however. Racial boundaries remained distinct and rules regarding the body types and sexuality of soldiers kept many men from succeeding along these lines or gaining the societal appreciation of other heterosexual, cissexual, white men. Racial minorities and men discharged for homosexual activity often received Blue Discharges, preventing them from receiving benefits from the Veterans Administration.

The characteristics and power dynamics of hegemonic males, though still remaining dominant decades later, were challenged and transformed in the 1960s by the sexual revolution, the African-American Civil Rights Movement, raised class consciousness, the re-entry of women into the workplace, the gay rights movement, the counter-culture, and the falling mystique of the military during and after the Vietnam War. However, contestation from these groups existed well before the 1960s, and the repeated affirmation of white, male, middle-class norms speaks volumes for the efforts of powerful institutions to keep these voices marginalized. I argue that the military drew upon these dominant concepts of power not only to exert their own power, both globally and locally, but to solidify the domestic power of the hegemonic male. However, military service and the military’s treatment of these groups, aided in organizing and fueling the pushback from many alternative identities and cultures in the years following the war.

About the Materials

The documents I examine are pulled from a wide range of sources and served a wide range of purposes. Though I was only able to peruse a small portion of the vast collection of government productions, I digitized every piece I came across that gave a strong gender representation amongst the male sex. The materials were created for a variety of purposes: some of the materials were only distributed to enlisted men, some were used for recruiting, and some were specifically targeted at women. These materials drew on emerging and popular media, including comic books and Hollywood-style films, and (often literally) paint a picture of the American soldier as an ideal male. Military comic books and other printed material with cartoon illustrations compose a large portion of my primary sources. Government comic books trace their roots back to the First World War, when propaganda creation was ramped up and these popular images became a key component to maintain support and morale.[^] The Committee on Public Information (CPI) was established in 1917, and in 1918, a Bureau of Cartoons was established within the CPI.[^]

The federal government’s interest in the power of cartoons to convey messages continued, and was amplified again when the nation once again went to war in Europe. In 1942, the Bureau of Intelligence (successor to the CPI) conducted analysis of newspaper cartoon strips for the OWI, and found that depictions of the enemy were too simplistic and could lead to overconfidence.[^] Graham wrote, “That the government believed in the persuasive power and mass appeal of comics is clear from the widespread use of the medium and its simultaneous suppression of the format.”[^] Graham added that the commercial comics industry bowed to government pressure to limit violence and promote American values, and began self-regulating in the 1950s.[^] Across the government comics, Graham found, “The government had certain ideals in mind with regard to what American culture was and ought to be, and it recognized the mass appeal of comics and their potential for getting those cultural messages across.”[^] These documents created the idea of what was to be expected of American GIs and shaped the way they were understood and framed within society. While I do not claim to know the motivations behind each of these artifacts, a critical analysis of them, along with a deep contextual understanding of the era, provide a useful examination of these propagandistic materials.

During World War Two, the Office of War Information (OWI) had a special media division for cartoons and comics, as did the individual branches of the military, and well-known artists, as well as enlistees, took part in producing cartoons conveying the federal government’s messages and visions.[^] During WWII and the postwar years, the federal government developed an extensive research budget to understanding the psychology and effective techniques behind propaganda and other kinds of psychological warfare. These tactics were undoubtedly put to work in the production of comics that took aim at a influencing a broad audience and large readership. Richard L. Graham, in his study of government comic books, Government Issue: Comics for the People, 1940-2000s, wrote, “Postwar military publications moved beyond the pocket-sized manuals and booklets printed for soldiers. From the 1950s onward, the armed forces published full-color comic books, such as Time of Decision (1963), designed to engage the newly emerging ‘youth culture.’”[^] These images were also distributed in nonmilitary culture, and became the normative imagery for the armed forces — promoting everything exclusively in positive light, with rampant heroism and flawless masculinity.

Brandon T. Locke | MA Student | University of Nebraska-Lincoln Department of History

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 United States License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 United States License.