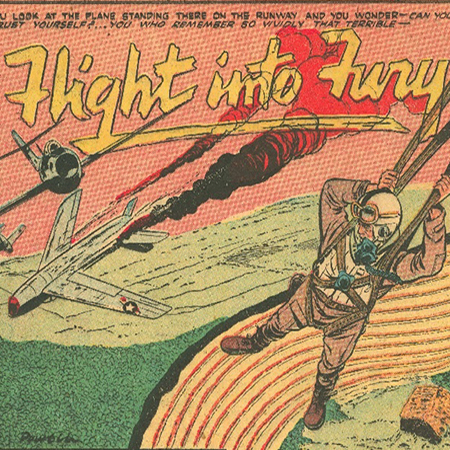

"Flight into Fury" in

The United States Marines No. 8

1952

David and Brannon argued that inexpressiveness and independence composed an essential dimension of manhood, the archetypal example of which they termed the “sturdy oak.” The dimension is defined as the maintenance of emotional composure and self control no matter what, and an unwavering drive to solve problems without help or showing weakness of any kind.[^] The term “sturdy oak” further relates the oppositional relationship the characteristic has with women: “The metaphor of the male as the ‘sturdy oak’ and the female as the ‘clinging vine’ has been a common one in America. Looking at an oak tree, one can see a solid trunk that will not bend with the wind, that will always be there, and that will give shelter to those who need it.”[^] The authors go on to write, “American men are supposed to be tough, confident, self-reliant, strong, independent, cool, determined, and unflappable.”[^] Sturdy oak characteristics are are most important and most visible in times of war and crisis, and these sheltering, stable male qualities were a large part of the masculine qualities applied to the nation during WWII and into the Cold War.

The sturdy oak has also been a key component of military masculinity for across different cultures, as Goldstein argued in War and Gender.[^] Given the militarized environment in which most of the DoD materials takes place, there is a great amount of overlap between Inexpressiveness and Independence and Aggressiveness and Adventurousness, where men are faced with danger and death, but fight on anyway. Therefore the stoicism and confidence that David and Brannon describe is innate and central in many of the works in the Aggressiveness and Adventurousness dimension. For the purposes of this project, I have separated the emphasis on a man’s ability to fight unflinchingly from an emphasis on the ability to show no emotion and stay composed. In this section, I will highlight the ways in which inexpressiveness is used to present a more cool and steeled man, in contrast to the Aggressiveness and Adventurousness, where this quality is shown to be a more heroic and valorous archetype.

The masculine archetype of being unemotional and inexpressive is bolstered by numerous example of men unaffected, and in many cases, seemingly unaware, of the death and destruction around them. While there are many times when the men respond to these kinds of hazardous conditions with aggression and heroism, there are also times where they just remain steely-eyed and push through. Sometimes they even make light of the situation and make jokes in the face of grave danger, illustrating how unaffected they are.

Stoicism was often manifest through humor in the face of danger in the 1952 publication Leatherhead in Korea, a collection of comedic cartoons originally published in the Marine Corps Gazette by Norvel E. Packwood. In a number of comics, he depicted the soldiers as able to act oblivious to enemy fire, and to make witty remarks or carry on with their casual conversations as though they were at no risk. Though done in jest, these depictions do carry with them an understanding that the men are fearless and cannot be rattled by anything. This presents a different sort of fearlessness than the comics in the Aggressiveness and Adventurousness section, but nonetheless offers a counter to men cowering in foxholes or running away from threats. Although this is certainly a less heroic or desirable form of stoicism, it reinforces the idea that these men do not feel emotion, or that they can hide their emotions and act as though nothing is wrong, even under the most dire and deadly situations.

When men in DoD publications were faced with serious threats, difficulty, and loss, the vast majority embodied the expectation of silent strength and emotional disconnect, though some acknowledged emotional pain. The DoD was conscious of the psychological trauma that was being experienced by the men, and did not actively criticize men who showed sorrow or required psychological help. At the same time, their depictions of men in entertainment media always displayed independence and courageousness alone as a cure to emotional trauma. The men who face difficulty do not seek out help from therapists, counselors, clergy, or senior officers, but instead bear down and fight through. It is telling, in this respect, that the pamphlet Builders of Faith: The moral and spiritual responsibilities of religious leaders and citizens of all faiths to young Americans in today’s world leaves out any mention of helping men with emotional problems or dealing with loss, despite the fact that it addresses a broad range of duties for clergy members, including their influence on the men’s spiritual growth and well being, community outreach, family structures and gender roles, and, most of all, preparing the men for the moral requirements of military service.[^]

The comic “Flight into Fury,” published in The United States Marines No. 8, is an intense second person narrative which places the reader in the shoes of a pilot about to embark on his first mission after being shot down over enemy territory.[^] The comic addresses issues of traumatic events and the questioning of one’s own abilities with some complexity and understanding. However, the story encourages Marines to ignore their fears, and to just simply bear down and act courageously and aggressively.

The comic opens with the protagonist, who is later referred to as Joe, standing on a runway wondering, “Can you trust yourself?…You who remember so vividly that terrible - Flight into Fury,” and begins walking the reader through the terrifying memories that haunt him.[^] More terrifying than the life-threatening events is reaction from others back home, and the damage caused to his reputation. The narration reads, “But mostly you remember the voices…the unheard voices that ran through your mind as you wandered around the base after returning to safety…” and a haunting dream sequence is shown across the panel, with disappointment, depression, mocking, and laughter.[^] A depressed man in shown drinking at a bar with his head in his hands, and a range of people, including associates, mechanics, a superior officer, and an enemy pilot all reinforcing the protagonist’s failures. He sees himself as a failure, and he presumes others do as well, and this is what leads him to question himself so intensely. This questioning, and the pressure from the presumed comments occurring behind his back, pushed him to request a transfer and start anew with a new unit.[^]

In the new unit, Joe was still gripped by his memories and fears of harm to his reputation. He questioned his own motives to reposition his unit, saying “Why don’t you face it? You’re not thinking of the men…you’re thinking of yourself. you’re afraid to tell them they have to withstand another attack like that! You’re a coward…A COWARD! A COWARD!!!!”[^] His decision to reposition was a costly one, and resulted in friendly fire between Joe’s unit and Marine reinforcements. His superior officer excoriates him, playing upon Joe’s self-doubt in saying, “…I don’t suppose it’s entirely your fault. A man with your record should never have been given such an assignment!”[^] This statement plays upon all of the protagonist’s fears and insecurities; the subsequent narration reads, ”A man with your record! The words burn into your memory…”[^]

The story then returns to the present, with Joe facing an opportunity to redeem himself. He spots an abandoned enemy plane and contemplates attacking the enemy artillery. He is forced to face his own insecurities, saying; “But do you have the courage? Can you step inside that thing and do the things you’re supposed to be able to do? Can you conquer your fears? Or are you going to be a coward all your life?”[^] Joe took the enemy plane into the air, eliminated enemy artillery, and shot down enemy planes, before crash landing. Joe woke up in a hospital to learn that his crew was able to hold out for reinforcements, all thanks to his heroism in the air.[^] The officer adds, “One thing I can’t understand, though, is how a guy who can fly like that didn’t stick to aviation,” prompting Joe to say that he found his own worst enemy, but “The guy is dead now…His name was Joe.”[^]

In “Flight into Fury,” like many of the DoD’s depictions of insurmountable odds, men were able to survive and triumph by staying in control, acting bravely, and fighting on. “Flight into Fury” deviates from this a bit by acknowledging and exploring the paralyzing fear and self-doubt one may encounter. However, the narrative encourages men to ignore these feelings and carry on without them. When Joe made a decision he felt was best, it backfired, and was attributed to his cowardice. When he put his feelings aside and did the “brave” thing, he helped the men in his unit and “killed” his own worst enemy; his own self-doubt.