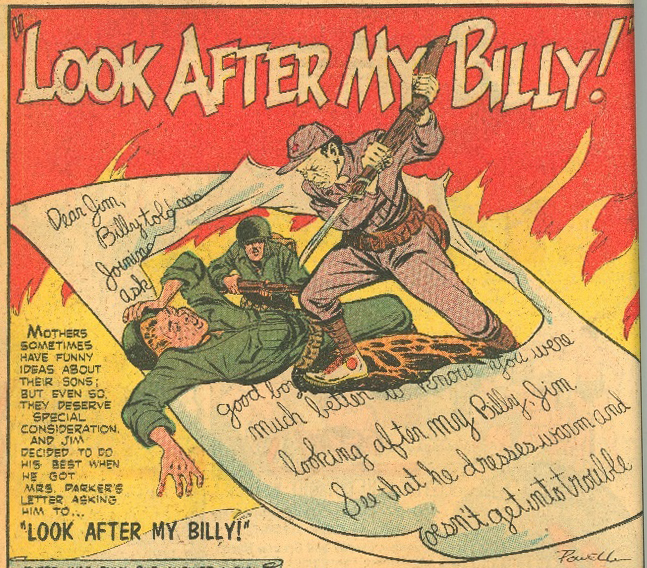

“Look After My Billy,” a comic piece in the 1952 publication The United States Marines No 7, is a short piece that addressed ‘momism,’ as well as the relationship men had with each other and their friends and family at home. The opening panel showed a handwritten letter with a Communist soldier about to bayonet a young, weak, and inept looking American soldier.[^] Behind them, a more mature, stronger looking GI is approaching, weapon in hand. The letter asks Jim to look after her Billy, and the caption begins, “Mothers sometimes have funny ideas about their sons…” Given the context, it’s rather clear that Billy is the weak, young GI, about to be killed in combat, who is inept and needs his mother to look after him.[^]

The story begins as Billy joins a military installment, and is obnoxious and overzealous, irritating many of his peers.[^] Billy rebuffs Jim for offering to look after him, as his mother has requested, and tells Jim that he will be playing craps for the rest of the night.[^] Billy continues to attempt to display his masculinity, as he cheats in the craps game, and then challenges a fellow soldier for accusing him of cheating.[^] He also frustrates his unit members with his false bravado and brags about his football abilities.[^]

Once the unit engages in battle, Billy is scared and completely frozen in place. He’s overwhelmed by the attacking force, and refuses to move until Jim smacks him hard across the face.[^] Here Jim is directly challenging his courage and masculinity through physical means, and it seemingly casts aside Billy’s fears and he agrees to move on.[^] Billy trips an attacker running into the trench, and then becomes enraged when Jim is stabbed with a bayonet.[^] Readers see Billy, now with a completely different demeanor and, for the first time, a straight and orderly helmet, saying, “Why, you dirty son-of-” and attacking the Communist soldier.[^]

In the next scene, readers see an officer telling Jim, “You’ve got Billy to thank for saving your life, Jim. I don’t know what came over him, but he held his position over three hours through four Commie charges, when they finally withdrew there were eleven bodies lying around him, and he was still fuming, standing over you like a watchdog!”[^] Billy comes to visit Jim in the hospital, and his bravado and arrogance are gone, and plans to refuse the Navy Cross for his actions.[^] He is embarrassed that he was a coward and ran away from combat. Billy was at first frozen by the horrors of war, but when is friend was hurt, he found a reserve of courage and defended him tenaciously. The story ends with Jim writing a letter to Billy’s mother, letting her know that Billy can look after himself, and that she need not worry about him again. The comic acknowledges the fear that men encounter in war, but also lays out a transformation that men can go through. The bookend correspondence with Billy’s mother really sets the tone for this transformation into adulthood – and more specifically, manhood.

This comes with some mixed messages regarding “Sissy Stuff.” On one hand, the narrative acknowledged that men are often scared, and may freeze or flee when placed into battle. As Jim says from the hospital bed, ”…You’re not the first guy who got scared of those Commie Advances. What counts is that you came through in the clutch! When you first came here, you weren’t a first class soldier because you hadn’t known fear. Now you know it…and I think you’ll be a different guy.”[^] Billy’s transformation here is made clear through means much more broad than simply being a good soldier. When Billy enters the service, he is full of false bravado, cowardly, and his mother must keep an eye over him. This immaturity presumably caused in part by “momism” and similar fears of feminization at the time. He was able to these flaws by battening down and responding to incoming threats and “knowing” (and ignoring) fear, and comes out more mature and humble.

Related Sections

- Inexpressiveness and Independence

- Inexpressiveness and Independence - Flight into Fury

- Inexpressiveness and Independence - Leatherhead in Korea

- Inexpressiveness and Independence - Marines No. 4

- Inexpressiveness and Independence - Victory at Gavutu

- Be a Big Wheel - Athletic & Physical Prowess - Look After My Billy!

Primary Sources