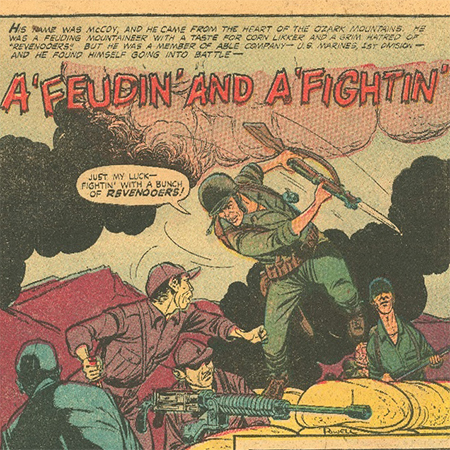

"A’feudin’ and A’fightin’," in The United States Marines No. 8

c1952

Brannon and David argue that masculinity is characterized by a willingness to take physical risks and become violent if it is deemed necessary.[^] This category, taken in its most broad definition, is ubiquitous to the DoD materials. Military service inherently involves adventurousness and aggression, and one should expect depictions of service to reflect that. Brannon and David’s definition places these traits in a more specific context, and require that they be used to certain ends. They argue that aggression (defined as an offensive action or procedure) and violence (defined as the exertion of any physical force to injure or abuse) stem, in part, from the need to win at any cost.[^] Brannon also importantly points out that the aura emphasis mine of aggression and violence increases one’s masculinity, even if one is never actually aggressive.[^] Joshua Goldstein, in his broad study of the intersections of gender and war across cultures, found that “…those parts of masculinity that are found most widely across cultures and time are not arbitrary but shaped but he war system.”[^] The cultural works produced by the military display daring and aggressiveness from American soldiers in a manner that is very much infused with conceptions of honor and valor, thus raising the infusing positive masculinity with military masculinity. At the same time, they produced examples of similar behavior from enemies that was strongly discouraged, and were very critical of the enemy soldiers performing essentially the same behaviors. Some documents also depicted American soldiers engaging in risky activities that did not advance the military’s purposes. These men were depicted in a negative light, and in some cases were expressly criticized and demeaned for their behavior. In sum, these pieces of media celebrated and encouraged acts of daring that benefitted the United States military, while discouraging and even demonizing acts that went counter to the military’s purposes.

The DoD materials attempt to carefully cultivate an honorable and productive aggression that best serves the nation. Courageous and honorable aggression were depicted, as men fought against long odds and risked their lives. These acts were encouraged, and were highly honored and glamorized in the media. These narratives ascribed culturally cherished notions of sacrifice for one’s nation, and courage in the face of adversity. They also inflated the idea that men in the military were of superior physical and moral strength.

It should be no surprise that depictions of battles in US publications would focus on American successes, and would portray soldiers in a positive light. However, these narratives fostered a mystique of superiority, and explicitly credited American soldiers with better fighting skills and a more impressive physical prowess. One such explicit example is the Navy comic Li’l Abner Joins the Navy!. The comic twice shows a small group of unimposing men assaulting and subduing larger groups of burly men. The central character is Drawin’-Board McEasel, an artist with small stature, oversized bow tie, and glasses who is introduced as “…not much to look at…”[^] When Drawin’-Board and a Navy recruiter are confronted with The Screwballs, a band of three burly criminals who are pillaging the town, the recruiter deputizes Drawin’-Board into the Navy, and the two quickly subdue the band of criminals.[^] The Screwballs are left laying on the ground, dazed and bruised, saying “Th’ yewnited states navy shore packs a wallop (groan!)” and “Ow! (sob!) must be a torpedo bashed may jaw!…” giving the Navy credit for the recruiter and Drawin’-Board’s ability to fight them off.[^]

Soon after, the Screwballs join up with two new associates and attempt to steal plans for a new Navy vehicle. The recruiter recognizes them, and with the help of Drawin’-Board and a white haired sailor named Salty McAnchor (who claims to have salt water on both knees), the three catch and subdue the would-be traitors, despite the physical and numerical disadvantage.[^] Their status as sailors is seemingly the only advantage they have, but it is enough to physically overpower them again. These events grant an unseen physical prowess to the sailors, one that can seemingly be attained by simply being deputized. This unseen advantage is, however, reinforced by the possibility of a physical advantage gained from joining the Navy. When Drawin’-Board is subduing the criminals, the recruiter imagines him as a unformed sailor, and the image he conjures is distinctly different from Drawin’-Board as he currently exists.[^] An enlisted Drawin’-Board is barrel-chested and standing proud, in contrast to the effete images that opened the story.

Beyond being physically superior, male soldiers were also shown as having an unflinching willingness to put their lives and well-being on the line for their nation. This not only encouraged men to act with the nation’s well-being ahead of their own, not simply self-preservation, and fostered the themes of honor and valor amongst soldiers and veterans. The United States Marines comic books were often loaded with short narratives of military battles where men came within inches of death and persevered against extremely long odds.

The comic “Tarawa,” in The United States Marines No. 3 is infused with positive depictions of men willingly risking their lives to take control of Tarawa in the Pacific. One panel shows two Marines charging over a hill, bayonets attached, conjuring notions of daring and aggressiveness.marines 3, p6 The caption reads, “Everywhere the Marines were eager to advance faster than was believed safe…”[^] While one Marine behind them is cautious, shouting, “Stay down, you guys!” another looks on, adding admiringly, “They go anywhere, those Marines!”[^] Here the author explicitly states that Marines willingly threw caution to the wind. They were eager to go at an unsafe speed and put their own well-being on the line. Near the end of the story, the Marines’ daring on this mission was again reinforced. A panel reads, “And so, seventy-six hours after the invasion began, Tarawa fell. The conquest was completed so quickly, as one observer said, because the Marines were willing to die unflinchingly.”[^] The willingness of the Marines to die is again credited with the speed of success, this time much more explicitly. Risky behavior and a lack of concern over one’s own well being is honored and celebrated. These two examples explicitly support and credit this quality, which is underwritten in nearly every depiction of battle.

Conceptions of aggression and courage through endangerment in white, middle-class masculinity were countered and balanced against conceptions of control and restraint. Aaron Belkin wrote, “The new code of middle-class masculinity that emerged at the end of the nineteenth century was structured by two, competing visions — primitive and civilized — which emphasized ruggedness and virility on one hand and order and control on the other.”[^] The order and control were largely the result of an emphasis on the rhetoric of civilization, which distinguished whites from racial and ethnic minorities, and reinforced racial discrimination and mistreatment.[^] In order to draw upon proper manhood and justify the use of violence and aggression, notions of control and constraint were infused into narratives.

The materials do not depict Americans being over-aggressive or brutal, and acts of cowardice are always redeemed later on. The materials fostered a popular conception of American soldiers as functioning within culturally acceptable lines of violence and warfare. This aura of controlled and proper aggression and violence was proscribed to all of the soldiers through this media, regardless of one’s actions – whether they saw action abroad or acted in ways deemed non-aggressive or cowardly. In reality, these limits were sometimes crossed, especially in the Pacific theater during World War II. American GIs sometimes mutilate corpses, took trophies, urinated or rape enemy combatants.[^] However, these materials contributed to the imagery of a just and honorable fighting force, and proscribed these traits to the population of those who served.

The aggression as put forth by the military during this time is one of restraint and control, and is only used when provoked. The comic Lil Abner Joins the Navy emphasizes the role of Navy men to be protectors of others, especially those seen as weaker or more innocent. The criminals, known as The Screwballs, knew that all the able-bodied men would be chased away by the women on Sadie Hawkins Day, so they came to steal everything from the old men and women left in town.[^] When Drawin’-Board and the recruiter fight back, they exclaim that they are taking the fight to the Screwballs’ “backyard.”[^] They even go so far as exclaiming “Remember Pearl Harbor!” when they attack the screwballs, recalling the ability of the US to respond to aggression when first attacked.[^] This concept is taken to the national level later on when the publication informs readers that, “The Navy is our best insurance to discourage a country from picking a fight with us…and if war does come, a strong Navy keeps destruction from our shores by carrying the battle to the enemy in his backyard!”[^] This echoes conceptions about middle class white masculinity, who prided themselves on restraint and non-aggression when unwarranted every bit as much as on paternalistic protection and aggressive capabilities.

Homer McCoy, the protagonist of ”A’feudin’ and a’fightin’,” illustrates this restraint as well, although he serves as a comedic foil. A moonshiner from the Ozark Mountains, McCoy excitedly joined the Marines to fight in the war, but became reluctant to fight once he learned that American involvement in Korea was not a war, but a “police action.”[^] After this realization, he reluctantly follows orders from the “revenooers” (drawing a connection between federal tax agents and this police action), but refuses to actively participate. is mindset drastically changes, however, when a grenade destroys his still. He exclaims, “Them Reds! Now I know who they are - they’re Hatfields! If’n there’s anybody a McCoy hates wors’n the revenooers — it’s them Hatfields all emphasis original”[^] McCoy then ”…fell on the Reds with the savage ferocity of a feuding mountaineer…” and charged the enemy, brutally killing two with his bayonet while screaming, “Varmits! Hatfields! Only scum like you would blow up a man’s still when he was pure dyin’ of thirst!”marines no8 p9 McCoy felt he had no issue with the Communist army until he thinks they destroyed his whiskey still, causing him to relentlessly attack them.[^] Although McCoy was a rube presented for comedic relief, he demonstrated extreme masculinity, both in his unwillingness to attack without provocation, as well as in his unrelenting aggression.

When acts of endangerment or aggression could potentially cause harm to the US armed forces, they were discouraged, mocked, and demeaned. These actions were also discursively detached from their masculine meanings. The two primary avenues for depictions of men illustrating aggression and adventurousness in ways that did not benefit the military came through servicemen injuring themselves outside of the battlefield, or instances of enemy heroism.

In attempts to foment and celebrate risky behavior for the men when it benefitted the nation, the Department of Defense went away from this masculine dimension in its purest form and criticized this adventurousness and risk when it could potentially harm the nation.

The 1944 Army pamphlet, Pvt. Droop has Missed the War!, warns soldiers of the risky behavior they must avoid in order to remain a part of the US military.[^] The pamphlet opens with Pvt. Droop in a hospital bed, and the line “When he gets out, he won’t be Pvt. Droop any more. He’ll be Mr. Droop - the army can’t use a man with a permanently wrecked leg.”[^] The statement is unfriendly toward his current status, and is condemning of his military status following his injury. The pamphlet goes on to say, “Did he fall on the field of battle on some far-off front? Was he trying to save a buddy under raking machine-gun fire? Nope! Pvt. Droop was hit by a truck while he was crossing a street in the middle of the block.”[^] The passages shames him for being hurt off the field of battle, and honors the ways in which soldiers could end up similarly disabled. They further shame him by adding, “He has missed the war — the war he wanted to fight. He has deserted, not from lack of patriotism, but from thought-lessness.”[^] The pamphlet went on to discourage numerous dangerous activities in which men may participate. These dangerous activities, the pamphlet conveyed, could result in a servicemen’s emasculation, or even a desertion of a man’s responsibilities.

Acts of over-the-top aggression, when performed by the enemy, were not depicted in the same heroic, masculine ways as those performed by Americans. In those situations, the enemy is shown as delusional or suicidal. This is a twofold blow to their masculinity, as honor and courage are removed, along with their agency. They are simply being controlled and manipulated by an outside entity, rather than defending their country by their own free will, as Americans are depicted.

In the publication The United States Marines, No. 4, the same serial that repeatedly touted Americans’ disregard for their own well-being, Japanese soldiers are mocked and demeaned for refusing to back down. In chronicling a successful US island invasion, the comic “Saipan!” wrote, “Many civilians on Saipan heeded the pleas of the Marines to surrender, but others, held by Jap fanaticism, committed hari-kiri sic or were killed by other Japs.”[^] On the following page, a panel shows a Japanese soldier rushing into a storm of enemy fire, screaming, ”BANZAI! Death to Molines!” with a Marine responding, “You got your facts twisted, Jappie.”[^]

These acts of resistance, ranging from civilians defending their homeland from foreign invaders to an enemy soldier disregarding his own well-being for the sake of his cause, would have been celebrated to no end if performed by an American. The latter situation, especially, is essentially the same story as those used to support American military aggression.[^] Additionally, the Japanese practice of hari-kari was just as courageous and honorable in Japanese culture as anything American soldiers did, but the practice was reframed as cowardly, and proof of this alleged fanaticism. Rather than recognizing and appreciating the heroism of these Japanese men, they are dismissed as being brainwashed by “Jap fanaticism.” Here they have no agency, but are simply being manipulated into losing their lives.