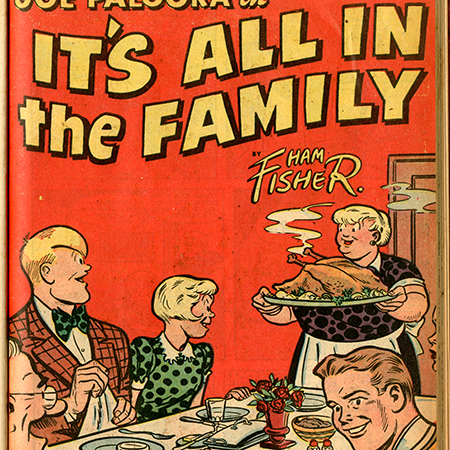

“It’s All in the Family,” in

Citizenship Booklet

c1951

The breadwinner role sat at the intersection of a man’s duties as a father and a man’s position in the workplace.[^] The breadwinner ethic combined the two roles most important to men on the homefront or during peacetime, and served as a key component of the way others judged him. During the postwar era, men were under great scrutiny for their abilities in both of these gendered arenas, and a large amount of discourse took place about proper masculinity, fatherhood, and the ability for a man to provide for his family. The military publications promote the idea that military men were exemplars of postwar masculinity, and could thrive in the gendered spheres that composed the breadwinner role.

Becoming a big wheel financially through military service was carefully depicted as a situation where a man could earn his benefits to financial success. Unlike the programs of the New Deal, which were often seen or demeaned as handouts or, in the case of the CCC and WPA, work created just to keep men busy. The military then became a more respectable avenue for a man to earn his education and training. This aligns with the central concept of the Self-Made Man, put forth by Michael Kimmel in Manhood in America.[^] Because of the central role the military was seen in providing essential security to the nation, along with longstanding respect and admiration for warrior culture, military service was an acceptable way to earn assistance from the federal government.

Many of the comics framed success by focusing traditional individualistic successes to contribute to the greater good. Michael Kimmel bases his influential book Manhood in America: A Cultural History around the centrality of ‘The Self-Made Man’ in American manhood.[^] Kimmel wrote, “This book is a history of the Self-Made Man – ambitious and anxious, creatively resourceful and chronically restive, the builder of culture and among the casualties of his own handiwork, a man who is, as the great French thinker Alexis de Tocqueville wrote in 1832, ‘restless in the midst of abundance.’”[^] Although the conformity and control of the military goes directly in the face of this ideal, it was accepted and celebrated via other masculine ideas. The acceptance of conformity, control, and pride in being one small piece of a giant conglomeration would not endure in private lives. The 1950s produced a large corpus of popular articles, literature, and film that harshly criticizes the conformity and perceived lack of purpose for the corporate men of the decade. However, these materials do attempt to inject a sense of pride in contributing to a larger cause at the cost of independence.

Adult suburban men in the 1950s, according to Robert Griswold, were expected to be “team players,” contributing to the needs of large organizations and embodying the organization’s social ethic and values.[^] This mindset was key for men as they navigated the duties of breadwinners. Families were becoming increasingly based upon companionship between the husband and wife, and men were encouraged to make sacrifices (namely, their time) for the good of the family. Additionally, middle class men were now often employed in bureaucratic governmental or corporate institutions, which did not afford as much agency, and often depended on sacrifice by all for the greater good. The “team player” ethic was primary to military training and experience, and instilled ideas of honor and independence in men, despite having strict control of their day-to-day lives.[^] The military productions touted the ways in which military service could prepare and aid men for this essential societal role, and also created an understanding that these skills and traits were imbued within all soldiers and veterans.

The military materials depicted successful breadwinners as normative, and intricately tied military service with a man’s breadwinning abilities. In post-war recruiting materials, especially, narratives relied upon anxieties about these roles to persuade readers. These materials also bolstered the gendered divisions in the home and workplace, depicting men and women fulfilling very distinct roles in the home, and often, though not always, supporting the idea that women are best suited in the home rather than the workplace.

Men during this time were under intense scrutiny for their abilities to succeed in their growing duties as fathers, as well as their position in the workplace. The need to balance workplace responsibilities with the family was challenging and full of conflict. Employment meant time away from the family, and changing cultural landscapes and upward mobility meant that children spent more time outside of the home as well. In the 1920s, cultural critics believed that new institutions that came with urbanization and industrialization, namely schools, factories, hospitals, welfare agencies, and juvenile courts, put public authority over realms that were previously internal to the family.[^] Though the term itself was not coined until 1942, the concept of ‘momism’ — feminization due to overbearing women — gained traction in academic and popular discourse in the 1930s, with continued blame placed upon industrialization and the absent father.[^] Through the Great Depression, concerns over feminization and male absenteeism continued, according to Griswold, even as fathers struggled or were unable to provide for their children or be a strong male role model, according to popular cultural definitions.[^] Griswold argued that the war played a large role in placing fatherhood as an essential component of the conservative family ideology that characterized the postwar years.[^] Griswold wrote, “By emphasizing the contributions of fathers to social order, democracy, middle-class capitalism, eugenic trends, personality development, and psychological health, family researchers, politicians, and ideologues reemphasized the importance of fatherhood after its decline in the 1930s. But they did so without challenging a sex-based division of labor that relegated women to the home and left men in control of political, economic, and social affairs.”[^] Military publications adjusted with the changing conceptions of masculinity that consisted of less industry and more white-collar work. Postwar recruiting materials - especially those of the Army and Navy - touted the skills and career prospects one could learn from time in the service.

The Department of Defense-sponsored comic, It’s All in the Family, sought to reinforce the importance of the family in American society, as well as illustrate the giving and charitable nature of Americans.[^] The title of the comic comes from a statement near the end of the comic: “Dictators have to smash family life…‘cause that’s where democracy is born…where kids learn to love it and understand it and practice it…It’s all in the family!”[^] Therefore, the comic puts forth an idealized form and function of a family, and then places the family at the center of the American Way and democratic ideology.

The family structure in It’s All in the Family is rigidly divided along gendered lines, whereas men are expected to make an income, while women are meant to encourage and serve them. The men fix things, take over the farm, and get jobs to support the family. The women cook, bring food to the table, and babysit. Though this division alone is not indicative of the breadwinner ethos, one passage does give credence to the idea that the male (monetized) role is legitimated and appreciated far more than the feminine (unpaid domestic) role. The woman who lives next door is going into labor and her husband is having trouble starting the car.[^] The kids all do their part to help them out, and the parents discuss how fantastic their kids are, based on their willingness to pitch in and help others.[^] As Mr. and Mrs. Palooka reflect on the selflessness of their children, they recall a Christmas when Rosie offered to give a doll to their neighbor, Joe volunteered to get a paper route, and his younger brother expressed interest to do the same when he got older.[^] The mother tells the father that he worked pretty hard himself in those days, to which he replies, “And you kept me from gettin’ discouraged! You kept me pluggin’ along…”[^] These two frames, side by side, describe a familial structure where it is the duty of males to earn money for the family, and the female’s duty to encourage them – not to work an equal or greater amount at a job or at home, but to keep the breadwinning husband from getting discouraged. These distinctly divided roles for genders, centered upon the leadership of the adult male and placed into a storyline that is set to depict an ideal family, and names the family as the key building block in which American democracy is built, places a great deal of social value and worth upon the adult male who can fulfill this role.

In addition to constructing idealistic families as centered upon a breadwinner, with others available for support, other materials directly endorsed the idea that a man must earn a good living to attain a wife and family. Five Years Later…Where Will You Be? was a 1962 Army recruitment comic that told the story of Bud, a young man whose inability to make plans threatened his financial future, as well as his future with his girlfriend, Mary Lou. At the beginning of the comic, Bud is depicted as immature, and unsure of his future. Mary Lou became very upset with Bud’s indecisiveness, especially regarding his plans after graduation and their future together.[^] Mary Lou tells Bud he’s not half grown up yet because of this indecisiveness, and makes more remarks later on, contrasting Bud’s indecisiveness with the way a secret agent in the film who “…made things happen.”[^] Mary Lou tells him she wants to go straight home, where she tells him not to call her until he’s changed his attitude.[^]

Mary Lou’s frustrations with Bud clearly threaten their relationship, and all revolve around Bud’s inability to make decisions or “make things happen.” This kind of language makes it clear that their relationship is on the rocks because of his shortcomings as a mature male who can make decisions and has some degree of financial security. Bud meets with his older brother and his friends, who encourage him to join the Army. Bud proudly tells Mary Lou that he plans to gain an income and training in the military, and find a job from there.[^] Building on this, he then tells her he has plans for them too, that involves an aisle.[^] This is to say, of course, that the marriage (or at least the future of the relationship ) is either incomplete or dependent upon Bud securing a steady income and being able to provide for the family.

This comic depicts supports the fundamental placement of the male breadwinner role in society, by depicting heterosexual relationships with the male’s career and earnings as central to the relationship. The comic Five Years Later plays on the appeal of the male breadwinner to women through the role of the breadwinner. Male financial ‘security’ – that is, a well-paying job capable of supporting a family – was given an elevated role in this piece.

The messages embedded in these publications promote the military as an effective way for men to attain the status of an effective breadwinner, while also endorsing and reifying the importance of the male breadwinner in American society.