16 Linking, Segmentation, and Alignment

Table of contents

- 16.1 Links

- 16.2 Pointing Mechanisms

- 16.3 Blocks, Segments, and Anchors

- 16.4 Correspondence and Alignment

- 16.5 Synchronization

- 16.6 Identical Elements and Virtual Copies

- 16.7 Aggregation

- 16.8 Alternation

- 16.9 Stand-off Markup

- 16.10 Connecting Analytic and Textual Markup

- 16.11 Module for Linking, Segmentation, and Alignment

- to link disparate elements using the xml:id attribute (section 16.1 Links);

- to link disparate elements without using the xml:id attribute (sections 16.2.1 Pointing Elsewhere, 16.2.3 W3C element() Scheme, and 16.2.4 TEI XPointer Schemes);

- to segment text into elements convenient for the encoder and to mark arbitrary points within documents (section 16.3 Blocks, Segments, and Anchors);

- to represent correspondence or alignment among groups of text elements, both those with content and those which are empty (section 16.4 Correspondence and Alignment);47

- to synchronize elements of a text, that is to represent temporal correspondences and alignments among text elements (section 16.5 Synchronization) and also to align them with specific points in time (section 16.5.2 Placing Synchronous Events in Time);

- to specify that one text element is identical to or a copy of another (section 16.6 Identical Elements and Virtual Copies);

- to aggregate possibly noncontinguous elements (section 16.7 Aggregation);

- to specify that different elements are alternatives to one another and to express preferences among the alternatives (section 16.8 Alternation);

- to store markup separately from the data it describes (section 16.9 Stand-off Markup);

- to associate segments of a text with interpretations or analyses of their significance (section 16.10 Connecting Analytic and Textual Markup).

These facilities all use the same set of techniques based on the W3C XPointer framework (Grosso et al. (eds.) (2003)) This provides a variety of schemes; the most convenient of which, and that recommended by these Guidelines, makes use of the global xml:id attribute, as defined in section 1.3.1.1 Global Attributes, and introduced in the section of v. A Gentle Introduction to XML titled Identifiers and indicators . When the linking module is included in a schema, the attribute class att.global is extended to include eight additional attributes to support the various kinds of linking listed above. Each of these attributes is introduced in the appropriate section below. In addition, for many of the topics discussed, a choice of methods of encoding is offered, ranging from simple but less general ones, which use attribute values only, to more elaborate and more general ones, which use specialized elements.

16.1 LinksTEI: Links¶

We say that one element points to others if the first has an attribute whose value is a reference to the others: such an element is called a pointer element, or simply a pointer. Among the pointers that have been introduced up to this point in these Guidelines are note, ref, and ptr. These elements all indicate an association between one place in the document (the location of the pointer itself) and one or more others (the elements whose identifiers are specified by the pointer's target attribute). The module described in this chapter introduces a variation on this basic kind of pointer, known as a link, which specifies both ‘ends’ of an association. In addition, we define a syntax for representing locations in a document by a variety of means not dependent on the use of xml:id attributes.

16.1.1 Pointers and LinksTEI: Pointers and Links¶

- ptr/ (pointer) defines a pointer to another location.

target specifies the destination of the pointer by supplying one or more URI References - ref (reference) defines a reference to another location, possibly modified by additional text or comment.

target specifies the destination of the reference by supplying one or more URI References - link/ defines an association or hypertextual link

among elements or passages, of some type

not more precisely specifiable by other elements.

targets specifies the identifiers of the elements or passages to be linked or associated.

- att.pointing defines a set of attributes used by all elements which point

to other elements by means of one or more URI references.

type categorizes the pointer in some respect, using any convenient set of categories. evaluate specifies the intended meaning when the target of a pointer is itself a pointer.

<ptr xml:id="sa-p2" target="#sa-p1"/>

As noted elsewhere, both target and targets attributes take as value one or more URI reference. In the simplest case, a URI reference might indicate an element in the current document (or in some other document) by supplying the value used for its global xml:id attribute. Pointing or linking to external documents and pointing and linking where identifiers are not available are implemented by more complex forms of URI references, as described below in section 16.2 Pointing Mechanisms.

16.1.2 Using Pointers and LinksTEI: Using Pointers and Links¶

<l>The Goddess smiles on Whig and Tory race,</l>

<l>

<note type="imitation" place="foot" anchored="false">

<bibl>Virg. Æn. 10.</bibl>

<quote>

<l>Tros Rutulusve fuat; nullo discrimine habebo.</l>

<l>—— Rex Jupiter omnibus idem.</l>

</quote>

</note>'Tis the same rope at sev'ral ends they twist,

</l>

<l>To Dulness, Ridpath is as dear as Mist)</l>

This use of the note element can be called implicit pointing (or implicit linking). It relies on the juxtaposition of the note to the text being commented on for the connection to be understood. If it is felt that the mere juxtaposition of the note to the text does not make it sufficiently clear exactly what text segment is being commented on (for example, is it the immediately preceding line, or the immediately preceding two lines, or what?), or if it is decided to place the note at some distance from the text, then the pointing or the linking must be made explicit. We now consider various methods for doing that.

<l>The Goddess smiles on Whig and Tory race,

<ptr rend="unmarked" target="#note3.284"/>

</l>

<l>'Tis the same rope at sev'ral ends they twist,</l>

<l>To Dulness, Ridpath is as dear as Mist)</l>

<note

xml:id="note3.284"

type="imitation"

place="foot"

anchored="false">

<bibl>Virg. Æn. 10.</bibl>

<quote>

<l>Tros Rutulusve fuat; nullo discrimine habebo.</l>

<l>—— Rex Jupiter omnibus idem.</l>

</quote>

</note>

<l xml:id="l3.284">The Goddess smiles on Whig and Tory race,</l>

<l xml:id="l3.285">'Tis the same rope at sev'ral ends they twist,</l>

<l xml:id="l3.286">To Dulness, Ridpath is as dear as Mist)</l>

<!-- ... -->

type="imitation"

place="foot"

anchored="false"

target="#l3.284">

<ref rend="sc" target="#l3.284">Verse 283–84.

<quote>

<l>——. With equal grace</l>

<l>Our Goddess smiles on Whig and Tory race.</l>

</quote>

</ref>

<bibl>Virg. Æn. 10.</bibl>

<quote>

<l>Tros Rutulusve fuat; nullo discrimine habebo.</l>

<l>—— Rex Jupiter omnibus idem. </l>

</quote>

</note>

- a pointer within one line indicates the note

- the note indicates the line

- a pointer within the note indicates the line

xml:id="n3.284"

type="imitation"

place="foot"

anchored="false">

<ref rend="sc" target="#l3.284">Verse 283–84.

<quote>

<l>——. With equal grace</l>

<l>Our Goddess smiles on Whig and Tory race.</l>

</quote>

</ref>

<bibl>Virg. Æn. 10.</bibl>

<quote>

<l>Tros Rutulusve fuat; nullo discrimine habebo.</l>

<l>—— Rex Jupiter omnibus idem. </l>

</quote>

</note>

<link targets="#n3.284 #l3.284"/>

xml:id="nt3.284"

type="imitation"

place="foot"

anchored="false">

<ref rend="sc" xml:id="r3.284" target="#l3.284">Verse 283–84.

<quote>

<l>——. With equal grace</l>

<l>Our Goddess smiles on Whig and Tory race.</l>

</quote>

</ref>

<!-- ... -->

</note>

<!-- ... -->

<link targets="#r3.284 #l3.284"/>

16.1.3 Groups of LinksTEI: Groups of Links¶

- linkGrp (link group) defines a collection of associations or hypertextual links.

- att.pointing.group defines a set of attributes common to all elements which

enclose groups of pointer elements.

domains optionally specifies the identifiers of the elements within which all elements indicated by the contents of this element lie. targFunc (target function) describes the function of each of the values of the targets attribute of the enclosed link, join, or alt tags.

- att.pointing defines a set of attributes used by all elements which point

to other elements by means of one or more URI references.

type categorizes the pointer in some respect, using any convenient set of categories.

The linkGrp element provides a convenient way of establishing a default for the type attribute on a group of links of the same type: by default, the type attribute on a link element has the same value as that given for type on the enclosing linkGrp.

<l xml:id="l2.80">Where from Ambrosia, Jove retires for ease.</l>

<!-- ... -->

<l xml:id="l2.88">Sign'd with that Ichor which from Gods distills.</l>

<!-- ... -->

<note xml:id="n2.79" place="foot" anchored="false">

<bibl>Ovid Met. 12.</bibl>

<quote xml:lang="la">

<l>Orbe locus media est, inter terrasq; fretumq;</l>

<l>Cœlestesq; plagas —</l>

</quote>

</note>

<note xml:id="n2.88" place="foot" anchored="false"> Alludes to <bibl>Homer, Iliad 5</bibl> ...

</note>

<link targets="#n2.79 #l2.79"/>

<link targets="#n2.88 #l2.88"/>

<link targets="#n3.284 #l3.284"/>

</linkGrp>

<!-- ... --><linkGrp type="imitation" domains="dunciad dunnotes">

<link targets="#n2.79 #l2.79"/>

<link targets="#n2.88 #l2.88"/>

<!-- ... -->

<link targets="#n3.284 #l3.284"/>

<!-- ... -->

</linkGrp>

Note that there must be a single parent element for each ‘domain’; if some notes are contained by a section with identifier dunnotes, and others by a section with identifier dunimits, an intermediate pointer must be provided (as described in section 16.1.4 Intermediate Pointers) within the linkGrp and its identifier used instead.

<link targets="#n2.79 #l2.79"/>

<link targets="#n2.88 #l2.88"/>

<!-- ... -->

<link targets="#n3.284 #l3.284"/>

<!-- ... -->

</linkGrp>

16.1.4 Intermediate PointersTEI: Intermediate Pointers¶

In the preceding examples, we have shown various ways of linking an annotation and a single verse line. However, the example cited in fact requires us to encode an association between the note and a pair of verse lines (lines 284 and 285); we call these two lines a span.

There are a number of possible ways of correcting this error: one could use the target attribute to indicate one end of the span and the special purpose targetEnd attribute on the note element to point to the other. Another possibility might be to create an element which represents the whole span itself and assign that an xml:id attribute, which can then be linked to the note and ref elements. This could be done using for example the lg element defined in section 3.12.1 Core Tags for Verse or the ‘virtual’join element discussed in section 16.7 Aggregation.

The all value of evaluate is used on the link element to specify that any pointer encountered as a target of that element is itself evaluated. If evaluate had the value none, the link target would be the pointer itself, rather than the objects it points to.

Where a linkGrp element is used to group a collection of link elements, any intermediate pointer elements used by those link elements should be included within the linkGrp.

16.2 Pointing MechanismsTEI: Pointing Mechanisms¶

- into documents other than the current document;

- to a particular element in a document other than the current document using its xml:id;

- to a particular element whether in the current document or not, using its position in the XML element tree;

- at arbitrary content in any XML document using TEI-defined XPointer schemes.

All TEI attributes used to point at something else are declared as having the datatype data.pointer, which is defined as a URI reference50; the cases so far discussed are all simple examples of a URI reference. Another familiar example is the mechanism used in XHTML to create represent hypertext links by means of the XHTML href attribute. A URI reference can reference the whole of an XML resource such as a document or an XML element, or a sub-portion of such a resource, identified by means of an appropriate fragment identifier. Technically speaking, the ‘fragment identifier’ is that portion of a URI reference following the first unescaped ‘#’ character; in practice, it provides a means of accessing some part of the resource described by the URI which is less than the whole.

The first three of the following subsections provide only a brief overview and some examples of the W3C mechanisms recommended. More detailed information on the use of these mechanisms is readily available elsewhere.

16.2.1 Pointing ElsewhereTEI: Pointing Elsewhere¶

Like the ubiquitous if misnamed XHTML pointing attribute href, the TEI pointing attributes can point to a document that is not the current document (the one that contains the pointing element) whether it is in the same local filesystem as the current document, or on a different system entirely. In either case, the pointing can be accomplished absolutely (using the entire address of the target document) or relatively (using an address relative to the current base URI in force). The ‘current base URI’ is defined according to Marsh 2001. In general the current base URI in force is the value of the xml:base attribute of the closest ancestor that has one. If there is none, the base URI is that of the current document.

W3C <ref target="http://www.w3.org/TR/xmlbase/">XML

Base</ref> recommendation.

of the <ref

target="file:///usr/share/common-licenses/GPL-2">GNU General Public License</ref>.

<graphic url="Images/compic.png"/>

<figDesc>The figure shows the page from the <title>Orbis

pictus</title> of Comenius which is discussed in the text.</figDesc>

</figure>

<head>On Ancient Persian Manners</head>

<p>In the very first story of <ref target="Sadi/gulistan.2.i.html">

<title>The Gulistan of

Sa'di</title>

</ref>,

Sa'di relates moral advice worthy of Miss Minners ...</p>

<!-- ... -->

</div>

<div n="A">

<p>The base URI here is the current document. A URI such as

<code>a.xml</code> is equivalent to

<code>./a.xml</code>.</p>

</div>

<div n="B" xml:base="http://www.example.org/">

<p>The base URI here is

<code>http://www.example.org/</code>. A

URI such as <code>a.xml</code> is equivalent to

<code>http://www.example.org/a.xml</code>.</p>

</div>

<div n="C" xml:base="ftp://ftp.example.net/mirror/">

<p>The base URI here is

<code>ftp://ftp.example.net/mirror/</code>. A URI such

as

<code>a.xml</code> is equivalent to

<code>ftp://ftp.example.net/mirror/a.xml</code>.</p>

</div>

<div n="D">

<p>The base URI here is the current document. A URI such as

<code>a.xml</code> is equivalent to

<code>./a.xml</code>.</p>

</div>

</body>

16.2.2 Pointing LocallyTEI: Pointing Locally¶

<!-- ... -->

</div>

<div type="section" n="107" xml:id="sect107">

<head>Limitations on exclusive rights: Fair use</head>

<p>Notwithstanding the provisions of

<ref target="#sect106">section 106</ref>, the fair use of a

copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies

or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section,

for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting,

teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use),

scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright.

In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular

case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall

include —

<list type="simple">

<item n="(1)">the purpose and character of the use, including

whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit

educational purposes;</item>

<item n="(2)">the nature of the copyrighted work;</item>

<item n="(3)">the amount and substantiality of the portion

used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole;

and</item>

<item n="(4)">the effect of the use upon the potential market

for or value of the copyrighted work.</item>

</list>

The fact that a work is unpublished shall not itself bar a

finding of fair use if such finding is made upon consideration

of all the above factors.</p>

</div>

16.2.3 W3C element() SchemeTEI: W3C element() Scheme¶

If elements are not directly addressable by means of an identifier, because no identifier was originally given to them and the document cannot be modified to add one, they may still be pointed to by means of their position in the XML element tree. This method of pointing uses the element() scheme defined by the World Wide Web Consortium (Grosso et al, 2003). In this scheme, an element may be identified by stepwise navigation using a slash-separated list of child element numbers. For each step the integer n locates the nth child element of the previously located element. Thus a pointer such as <ptr target="foo.xml#element(/1/4)"/> indicates the fourth child element starting from the root element of the document indicated by the URI foo.xml.

target="http://www.cs.mu.oz.au/621/2003project/hamlet.xml#element(/1/8/2/25/2)">2B|^2B…</ref>

xml:base="/Users/martin/Documents/c5/namelessShakespeare.xml">

<p>

<ptr target="#element(sha-ham301/22/2)"/>

</p>

</div>

As noted above, we could also point directly to this line if it had an identifier of its own. In another digital edition of Shakespeare, based on the first folio, each line is given an identifier based on its ‘through line number’. Our pointer to this line can now be represented simply as <ptr target="#element(Ham01245)"/>, or even more simply as <ptr target="#Ham01245"/>. The notation <ptr target="#xxx"/> is a convenient abbreviation for <ptr target="#element(xxx)"/>. This method requires, of course, that the ‘Through Line Number’ is supplied as the value of an xml:id attribute on each line, and must therefore be unique within each document. In section 16.2.5 Canonical References we discuss a method of pointing to the line which does not have this requirement.

16.2.4 TEI XPointer SchemesTEI: TEI XPointer Schemes¶

The pointing scheme described in this chapter is one of a number of such schemes envisaged by the W3C, which together constitute a framework for addressing data within XML documents, known as the XPointer Framework (Grosso et al 2003). This framework permits the definition of many other named addressing methods, each of which is known as an XPointer Scheme. The W3C has predefined a set of such schemes, and maintains a register for their expansion. The element() scheme described above is one such scheme, defined by the W3C, and widely implemented by XML processing systems.

Another important scheme, also defined by the W3C, and recommended by these Guidelines is the xpath1() pointer scheme, which allows for any part of an XML structure to be selected using the syntax defined by the XPath specification. This is further discussed below, 16.2.4.2 xpath1(Expr). These Guidelines also define five other pointer schemes, which provide access to parts of an XML document such as points within data content or stretches of data content. These additional TEI pointer schemes are defined in sections 16.2.4.3 left(pointer) and right(pointer) to 16.2.4.6 match(pointer, string [, index]) below.

16.2.4.1 Introduction to TEI PointersTEI: Introduction to TEI Pointers¶

Before discussing the TEI pointer schemes, we introduce slightly more formally the terminology used to define them. So far, we have discussed only ways of pointing at components of the XML information set node such as elements and attributes. However, there is often a need in text analysis to address additional types of location such as the ‘point’ locations between nodes, and ‘ranges’ that may arbitrarily cross the boundaries of nodes in a document. The content of an XML document is organized sequentially as well as hierarchically, and it therefore makes sense to consider ranges of characters within it independently of the nodes to which they belong, for example when making a selection in a text editor. For processing purposes, such a range is best defined by the pair of points at its start and end. It is often useful to think of pointer schemes as analogous to query functions that return nodes in the XML information set (the DOM tree) of an XML document, as in the case of the element and xpath pointer schemes discussed so far, but this is not invariably the case. A point is adjacent to one or two nodes, but is not a node itself, while a range may not even overlap with any complete node in the DOM tree.

- Node

- A node represents a single item in the XML information set for a document. For pointing purposes, the only nodes that are of interest are Text Nodes, Element Nodes, and Attribute nodes.

- Node Set

- A node set is a set of nodes in the XML information set of a document. In TEI Pointing applications, node sets are only allowed as the result of resolving a URI when multiple URIs would have been allowed where it appears, i.e. in attributes which are declared as permitting two or more data.pointer values as opposed to only one. As the name ‘set,’ implies, the individual items in a node set are not ordered, and no assumptions about relative ordering of items in a node set should be made.

- Point

- A Point represents a point between nodes in a document.

Every point is adjacent to either characters or elements, and

never to another point. In fact, in the character

representation of an XML document, every position between data

characters, start-tags or end-tags is a point, and there are

no other points.

If one treats all character content as if it were broken into

single-character text-nodes, every point is definable as either

- the point preceding a node, and if that node has a predecessor in document order, then it is the same as the point following that predecessor; or

- the point following a node, and if that node has a successor in document order, then it is the same as the point preceding that successor.

- Range

- A Range is defined as the portion of a document between two points. Since points may occur anywhere within the document, ranges do not correspond directly to nodes or to node sets. A range may overlap the contents of a node either completely or partially.

- xpath1()

- Addresses a node or nodeset using the XPath syntax. (16.2.4.2 xpath1(Expr))

- left() and right()

- addresses the point before (left) or after (right) a node or node set (16.2.4.3 left(pointer) and right(pointer))

- range()

- addresses the range between two points (16.2.4.4 range(pointer1, pointer2))

- string-range()

- addresses a range of a specified length starting from a specified point (16.2.4.4 range(pointer1, pointer2))

- match()

- addresses a range which matches a specified string within a node (16.2.4.6 match(pointer, string [, index]))

The xpath1() scheme refers to the existing XPath specification which is adopted without modification or extension.

The other five schemes overlap in functionality with a W3C draft specification known as the XPointer scheme draft, but are individually much simpler. At the time of this writing, there is no current or scheduled activity at the W3C towards revising this draft or issuing it as a recommendation.

16.2.4.2 xpath1(Expr)TEI: xpath1(Expr)¶

target="http://tinyurl.com/267z62/xml/2004/Thompson01/EML2004Thompson01.xml#xpath1(//ftnote[@id='fn6']/para[1])"/>

When a URI reference is specified as the value of an attribute declared as a single data.pointer value, the result must be a single node, and it is an error if the result is a node set. When the URI reference is specified as the value of an attribute declared to permit two or more data.pointer values, each node in the node set is treated as if it were the result of a separate URI reference.

When an xpath is interpreted by a TEI processor, the information set of the referenced document is interpreted without any additional information supplied by any schema processing that may or may not be present. In particular this means that no whitespace normalization is applied to a document before the xpath is interpreted.

This pointer scheme allows easy, direct use of the most widely-implemented XML query method. It is probably the most robust pointing mechanism for the common situation of selecting an XML element or its contents where an xml:id is not present. The ability to use element names and attribute names and values makes xpath1() pointers more robust than the other mechanisms discussed in this section even if the designated document changes. For durability in the presence of editing, use of xml:id is always recommended when possible.

16.2.4.3 left(pointer) and right(pointer)TEI: left(pointer) and right(pointer)¶

- A Node

- When pointer resolves to a node, the point designated is the point immediately preceding (left()) or following (right()) the node.

- A Node Set

- When pointer resolves to a node set, the point designated is the point preceding the first element of the set (left()) or following the last element of the set (right())

- A range

- When pointer resolves to a range, the point designated is the point designating the start (left()) or end (right()) of the range.

- A Point

- When pointer resolves to a point, that point is the result. The pointer schemes left() and right() make no change when given a point as argument.

xml:base="http://www.mulberrytech.com/Extreme/Proceedings/xml/2002/">

<ptr

target="Usdin01/EML2002Usdin01.xml#right(element(/1/1/3/3/6))"/>

</p>

16.2.4.4 range(pointer1, pointer2)TEI: range(pointer1, pointer2)¶

- A Node

- When pointer1 resolves to a node, the starting point of the range is the point immediately preceding the node. When pointer2 resolves to a node, the ending point of the range is the point immediately following the node. It is an error if the ending point precedes the starting point of a range.

- A range

- When pointer1 resolves to a range R, the starting point of the result range is the same as the starting point of R. When pointer2 resolves to a range R, the ending point of the result range is the ending point of R.

- A Point

- When pointer1 resolves to a point, that point is the start of the range. When pointer2 resolves to a point, that point is the end of the range.

16.2.4.5 string-range(pointer, offset [, length])TEI: string-range(pointer, offset [, length])¶

The string-range() scheme locates a range based on character positions. While string-range endpoints are points adjacent to character positions, they must be designated by the characters to which they are adjacent, in the same way that the nodes corresponding to XML elements are. This avoids ambiguity about which point between two characters is indicated when characters are interrupted by markup.

The pointer argument to string-range() designates a node or a range within which a string is to be located. No string range, even an empty one, can be defined by a string-range() if pointer has the empty string as string value. Every string-range is defined based on an ‘origin character’. The origin is numbered 0, and designates the first character of the string-value of pointer. The offset is a character index relative to the origin; the start of the resulting range is the position designated by the sum of the origin and offset.

If length is specified, the end of the range is at a point adjacent to the character designated by the origin added to the offset and length. If the offset is negative, or length is sufficiently large, a string-range can designate characters outside the string-value of the intitial pointer. In this case, characters are located using the string-value of the entire document. It is also legal for length plus the origin to exceed the length of the string-value of the document by one, in order to accommodate ranges that include the last character of a document.

If length is not specified, it defaults to the value 1, and the string range contains one character. If it is specified as 0, the zero-length range is interpreted as the point immediately preceding the origin character or offset character if there is one.

16.2.4.6 match(pointer, string [, index])TEI: match(pointer, string [, index])¶

The match scheme designates the result of a literal match of the argument string within the string-value of the pointer argument. The result is a range from the first matching character to the last. It is an error if there is no matching string. A match may not extend outside the range corresponding to the string value of pointer.

The index argument is an integer greater than or equal to 1, specifying which match should be chosen when there is more than one match within the string-value of pointer. If no index is provided, the default value is 1, indicating the first match found.

16.2.5 Canonical ReferencesTEI: Canonical References¶

By ‘canonical’ reference we mean any means of pointing into documents, specific to a community or corpus. For example, biblical scholars might understand ‘Matt 5:7’ to mean ‘the book called Matthew, chapter 5, verse 7.’ They might then wish to translate the string ‘Matt 5:7’ into a pointer into a TEI-encoded document, selecting the element which corresponds to the seventh div element within the fifth div element within the div element with the n attribute valued ‘Matt.’

Several elements in the TEI scheme (gloss, ptr, ref, and term) bear a special attribute, cRef, just for this purpose. Using the system described in this section, an encoder may specify references to canonical works in a discipline-familiar format, and expect software to derive a complete URI from it. The value of the cRef attribute is processed as described in this section, and the resulting URI reference is treated as if it were the value of the target attribute. The cRef and target attributes are mutually exclusive: only one or the other may be specified on any given occurrence of an element.

<cRefPattern

matchPattern="(.+) (.+):(.+)"

replacementPattern="#xpath1(//div[@n='$1']/div[$2]/div[$3])">

<p>This pointer pattern extracts and references the <q>book,</q>

<q>chapter,</q> and <q>verse</q> parts of a biblical reference.</p>

</cRefPattern>

<cRefPattern matchPattern="(.+) (.+)"

replacementPattern="#xpath1(//div[@n='$1']/div[$2])">

<p>This pointer pattern extracts and references the <q>book</q> and

<q>chapter</q> parts of a biblical reference.</p>

</cRefPattern>

<cRefPattern matchPattern="(.+)"

replacementPattern="#xpath1(//div[@n='$1'])">

<p>This pointer pattern extracts and references just the <q>book</q>

part of a biblical reference.</p>

</cRefPattern>

</refsDecl>

- Ascertain the correct refsDecl following the rules summarized in section 15.3.3 Summary.

- For each cRefPattern element encountered in

the appropriate refsDecl, in the order encountered:

- match the value of cRef to the regular expression found as the value of the matchPattern attribute

- if the cRef value matches, take the value of the replacementPattern attribute and substitute the back references ($1, $2, etc.) with the corresponding matched substrings

- the result is taken as if it were a relative or absolute URI reference specified on the target attribute; i.e., it should be used as is or combined with the current xml:base value as usual

- no further processing of this cRef against the refsDecl should take place

- if, however, the cRef value does not match the regular expression specified on matchPattern attribute, proceed to the next cRefPattern

- If all the cRefPattern elements are examined in turn and none matches, the pointer fails.

The regular expression language used as the value of the matchPattern attribute is that used for the pattern facet of the World Wide Web Consortium's XML Schema Language in an Appendix to XML Schema Part 2.53 The value of the replacementPattern attribute is simply a string, except that occurences of ‘$1’ through ‘$9’ are replaced by the corresponding substring match. Note that since a maximum of nine substring matches are permitted, the string ‘$18’ means ‘the value of the first matched substring followed by the character ‘8’’ as opposed to ‘the eighteenth matched substring’. If there is a need for an actual string including a dollar sign followed by a digit that is not supposed to be replaced, the dollar sign should be written as %24.

16.2.5.1 Worked ExampleTEI: Worked Example¶

Let us presume that with the example refsDecl above, an application comes across a cRef value of Matt 5:7 inside a div which has an xml:base of http://www.example.org/resources/books/Bible.xml. The application would first apply the regular expression (.+) (.+):(.+) to ‘Matt 5:7’. This regular expression would successfully match. The first matched substring would be ‘Matt’, the second ‘5’, and the third ‘7’. The application would then apply these substrings to the pattern #xpath1(//div[@n='$1']/div[$2]/div[$3]), producing #xpath1(//div[@n='Matt']/div[5]/div[7]). It would append this to the xml:base in force, thus generating the complete URI Reference http://www.example.org/resources/books/Bible.xml#xpath1(//div[@n='Matt']/div[5]/div[7]).

If, however, the input string had been ‘Matt 5’, the first regular expression would not have matched. The application would have then tried the second, (.+) (.+), producing a successful match, and the matched substrings ‘Matt’ and ‘5’. It would then have substituted those matched substrings into the pattern #xpath1(//div[@n='$1']/div[$2]) to produce a fragment identifier, which when appended to the xml:base in force produces the absolute URI reference http://www.example.org/resources/books/Bible.xml#xpath1(//div[@n='Matt']/div[5]).

If the input string had been ‘Matt’, neither the first nor the second regular expressions would have successfully matched. The application would have then tried the third, (.+), producing the matched substring ‘Matt’, and the URI Reference http://www.example.org/resources/books/Bible.xml#xpath1(//div[@n='Matt']).

matchPattern="(.+) (.+):(.+)"

replacementPattern="//div[@n='$1']/div[$2]/div[$3]/p[$4]"/>

It is quite reasonable to believe that encoders would actually prefer much more precise regular expressions than those used as examples above. E.g., ^\s*([1-9]?[A-Z][a-z]+)\s+([1-9][0-9]?[0-9]?):([1-9][0-9]?)\s*$.

16.2.5.2 Complete and Partial URI ExamplesTEI: Complete and Partial URI Examples¶

<cRefPattern

matchPattern="([0-9][0-9])\s*U\.?S\.?C\.?\s*[Cc](h(\.|ap(ter|\.)?)?)?\s*([1-9][0-9]*)"

replacementPattern="http://uscode.house.gov/download/pls/$1C$5.txt">

<p>Matches most standard references to particular

chapters of the United States Code, e.g.

<val>11USCC7</val>, <val>17 U.S.C. Chapter 3</val>, or

<val>14 USC Ch. 5</val>. Note that a leading zero is

required for the title (must be two digits), but is not

permitted for the chapter number.</p>

</cRefPattern>

<cRefPattern

matchPattern="([0-9][0-9])\s*U\.?S\.?C\.?\s*[Pp](re(lim(inary)?)?)?\s*[Mm](at(erial)?)?"

replacementPattern="http://uscode.house.gov/download/pls/$1T.txt">

<p>Matches references to the preliminary material for a

given title, e.g. <val>11USCP</val>, <val>17 U.S.C.

Prelim Mat</val>, or <val>14 USC pm</val>.</p>

</cRefPattern>

<cRefPattern

matchPattern="([0-9][0-9])\s*U\.?S\.?C\.?\s*[Aa](ppend(ix)?)?"

replacementPattern="http://uscode.house.gov/download/pls/$1A.txt">

<p>Matches references to the appendix of a given tile,

e.g. <val>05USCA</val>, <val>11 U.S.C. Appendix</val>,

or <val>18 USC Append</val>.</p>

</cRefPattern>

</refsDecl>

<!-- ... -->

<p>The example in section <ptr target="#SABN"/> is taken

from <ref cRef="17 USC Ch 1">Subject Matter and Scope of

Copyright</ref>.</p>

16.2.5.3 Miscellaneous UsagesTEI: Miscellaneous Usages¶

Canonical reference pointers are intended for use by TEI encoders. However, this specification might be useful to the development of a process for recognizing canonical references in non-TEI documents (such as plain text documents), possibly as part of their conversion to TEI.

16.3 Blocks, Segments, and AnchorsTEI: Blocks, Segments, and Anchors¶

- anchor/ (anchor point) attaches an identifier to a point within a text, whether or not it corresponds with a textual element.

- ab (anonymous block) contains any arbitrary component-level unit of text, acting as

an anonymous container for phrase or inter level elements analogous to, but

without the semantic baggage of, a paragraph.

part specifies whether or not the block is complete.

- att.typed provides attributes which can be used to classify or subclassify elements in any way.

type characterizes the element in some sense, using any convenient classification scheme or typology. subtype provides a sub-categorization of the element, if needed

- att.segLike provides attributes for elements used for arbitrary segmentation.

function characterizes the function of the segment. part specifies whether or not the segment is fragmented by some other structural element, for example a clause which is divided between two or more sentences.

The anchor element may be thought of as an empty seg, or as an artifice enabling an identifier to be attached to any position in a text. Like the milestone element discussed in section 3.10 Reference Systems, it is useful where multiple views of a document are to be combined, for example, when a logical view based on paragraphs or verse lines is to be mapped on to a physical view based on manuscript lines. Like those elements, it is a member of the class model.global and can therefore appear anywhere within a document when the module defined by this chapter is included in a schema. Unlike the other elements in its class, the anchor element is primarily intended to mark an arbitrary point used for alignment, or as the target of a spanning element such as those discussed in section 11.3.4 Additions and Deletions, rather than as a means of marking segment boundaries for some arbitrary segmentation of a text.

English at all at the time<anchor xml:id="eng2"/>

English was still full of flaws<anchor xml:id="eng3"/>

English. This was revised by young

<anchor xml:id="eng4"/>

The seg element may be used at the encoder's discretion to mark almost any segment of the text of interest for processing. One use of the element is to mark text features for which no appropriate markup is otherwise defined, i.e. as a simple extension mechanism. Another use is to provide an identifier for some segment which is to be pointed at by some other element, i.e. to provide a target, or a part of a target, for a ptr or other similar element.

- as a means of marking segments significant in a metrical or rhyming analysis (see section 6.3 Rhyme and Metrical Analysis)

- as a means of marking typographic lines in drama (see section 7.2 The Body of a Performance Text) or title pages (see section 4.6 Title Pages)

- as a means of marking prosody- or pause-defined units in transcribed speech (see section 8.4.1 Segmentation)

- as a means of marking linguistic or other analyses in a theory-neutral manner (see chapter 17 Simple Analytic Mechanisms passim)

<seg type="stutter">I-I-I</seg>'m afraid,</q> Melvin, just say <q>I'm

afraid.</q>

</q>

<seg xml:id="bl0034.1" type="phrase">Literate and illiterate speech</seg>

<seg xml:id="bl0034.2" type="phrase">in a language like English</seg>

<seg xml:id="bl0034.3" type="phrase">are plainly different.</seg>

</seg>

<seg type="phrase" subtype="noun">

<seg type="word" subtype="adjective">Literate</seg>

<seg type="word" subtype="conjunction">and</seg>

<seg type="word" subtype="adjective">illiterate</seg>

<seg type="word" subtype="noun">speech</seg>

</seg>

<seg type="phrase" subtype="preposition">

<seg type="word" subtype="preposition">in</seg>

<seg type="word" subtype="article">a</seg>

<seg type="word" subtype="noun">language</seg>

<seg type="word" subtype="preposition">like</seg>

<seg type="word" subtype="noun">English</seg>

</seg>

<seg type="phrase" subtype="verb">

<seg type="word" subtype="verb">are</seg>

<seg type="word" subtype="adverb">plainly</seg>

<seg type="word" subtype="adjective">different</seg>

</seg>

<seg type="punct">.</seg>

</seg>

<w type="adjective">Literate</w>

<w type="conjunction">and</w>

<w type="adjective">illiterate</w>

<w type="noun">speech</w>

</phr>

<s xml:id="s1">Sigmund, the <seg type="patronymic">son of Volsung</seg>,

was a king in Frankish country.</s>

<s xml:id="s2">Sinfiotli was the eldest of his sons.</s>

<s xml:id="s3"> ... </s>

</seg>

</s>

<s>

<seg part="F">Or two or three.</seg>

</s>

The seg element has the same content as a paragraph in prose: it can therefore be used to group together consecutive sequences of model.inter class elements, such as lists, quotations, notes, stage directions, etc. as well as to contain sequences of phrase-level elements. It cannot however be used to group together sequences of paragraphs or similar text units such as verse lines; for this purpose, the encoder should use intermediate pointers, as described in section 16.1.4 Intermediate Pointers or the methods described in section 16.7 Aggregation. It is particularly important that the encoder provide a clear description of the principles by which a text has been segmented, and the way in which that segmentation is represented. This should include a description of the method used and the significance of any categorization codes. The description should be provided as a series of paragraphs within the segmentation element of the encoding description in the TEI header, as described in section 2.3.3 The Editorial Practices Declaration.

The seg element may also be used to encode simultaneous or mutually exclusive variants of a text when the more special purpose elements for simple editorial changes, abbreviation and expansion, addition and deletion, or for a critical apparatus are not appropriate. In these circumstances, one seg is encoded for each possible variant, and the set of them is enclosed in a choice element.

<seg type="platform" subtype="Mac">option</seg>

<seg type="platform" subtype="PC">alt</seg>

</choice>-f will …

Elsewhere in this chapter we provide a number of examples where the seg element is used simply to provide an element to which an identifier may be attached, for example so that another segment may be linked or related to it in some way.

The ab (anonymous block) element performs a similar function to that of the seg element, but is used for portions of the text which occur not within paragraphs or other component-level elements, but at the component level themselves. It is therefore a member of the model.pLike class.

<head>The First Book of Moses, Called</head>

<head type="main">Genesis</head>

<div2 n="1" type="chapter">

<ab n="1">In the beginning God created the heaven and the

earth.</ab>

<ab n="2">And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness

<hi>was</hi> upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God

moved upon the face of the waters.</ab>

<ab n="3">And God said, Let there be light: and there was

light.</ab>

</div2>

</div1>

<head>Das Erste Buch Mose.</head>

<div2 n="1" type="chapter">

<p>

<seg n="1">Am Anfang schuff Gott Himel vnd Erden.</seg>

<seg n="2">Vnd die Erde war wüst vnd leer / vnd es war

finster auff der Tieffe / Vnd der Geist Gottes schwebet auff

dem Wasser.</seg>

</p>

<p>

<seg n="3">Vnd Gott sprach / Es werde Liecht / Vnd es ward

Liecht.</seg>

</p>

</div2>

</div1>

<div2 n="1" type="scene">

<head rend="italic">Actus primus, Scena prima.</head>

<stage rend="italic" type="setting"> A tempestuous noise of

Thunder and Lightning heard:

Enter a Ship-master, and a Boteswaine.</stage>

<sp>

<speaker>Master.</speaker>

<ab>Bote-swaine.</ab>

</sp>

<sp>

<speaker>Botes.</speaker>

<ab>Heere Master: What cheere?</ab>

</sp>

<sp>

<speaker>Mast.</speaker>

<ab>Good: Speake to th' Mariners: fall too't, yarely,

or we run our selues a ground, bestirre, bestirre.

<stage type="move">Exit.</stage>

</ab>

</sp>

<stage type="move">Enter Mariners.</stage>

<sp>

<speaker>Botes.</speaker>

<ab>Heigh my hearts, cheerely, cheerely my harts: yare, yare:

Take in the toppe-sale: Tend to th' Masters whistle: Blow

till thou burst thy winde, if roome e-nough.</ab>

</sp>

</div2>

</div1>

16.4 Correspondence and AlignmentTEI: Correspondence and Alignment¶

In this section we introduce the notions of correspondence, expressed by the corresp attribute, and of alignment, which is a special kind of correspondence involving an ordered set of correspondences. Both cases may be represented using the link and linkGrp elements introduced in section 16.1 Links. We also discuss the special case of alignment in time or synchronization, for which special purpose elements are proposed in section 16.5 Synchronization.

16.4.1 CorrespondenceTEI: Correspondence¶

- att.global.linking defines a set of attributes for hypertext and other linking,

which are enabled for all elements when the additional tag set for

linking is selected.

corresp (corresponds) points to elements that correspond to the current element in some way.

Where the correspondence is between spans, the seg element should be used, if no other element is available. Where the correspondence is between points, the anchor element should be used, if no other element is available.

its Friday night debut only a month ago, was

not listed on <name xml:id="NBC">NBC</name>'s new schedule,

although <seg corresp="#NBC" xml:id="NETWORK">the network</seg>

says <seg corresp="#SHIRLEY" xml:id="SHOW">the show</seg>

still is being considered.

its Friday night debut only a month ago, was not

listed on <name xml:id="nbc">NBC</name>'s new schedule,

although <seg xml:id="network">the network</seg> says

<seg xml:id="show">the show</seg> still is being considered.

<linkGrp type="anaphoric_link" targFunc="antecedent anaphor">

<link targets="#shirley #show"/>

<link targets="#nbc #network"/>

</linkGrp>

16.4.2 Alignment of Parallel TextsTEI: Alignment of Parallel Texts¶

Most English sentences match exactly one French sentence, but it is possible for an English sentence to match two or more French sentences. The first two English sentences [in the example below] illustrate a particularly hard case where two English sentences align to two French sentences. No smaller alignments are possible because the clause ‘...sales...were higher...’ in the first English sentence corresponds to (part of) the second French sentence. The next two alignments ... illustrate the more typical case where one English sentence aligns with exactly one French sentence. The final alignment matches two English sentences to a single French sentence. These alignments [which were produced by a computer program] agreed with the results produced by a human judge.56

The alignment produced by Gale and Church's program can be expressed in four different ways. The encoder must first decide whether to represent the alignment in terms of points within each text (using the anchor element) or in terms of whole stretches of text, using the seg element. To some extent the choice will depend on the process by which the software works out where alignment occurs, and the intention of the encoder. Secondly, the encoder may elect to represent the actual encoding using either corresp attributes attached to the individual anchor or seg elements, or using a free standing linkGrp element.

<p>

<anchor corresp="#fa1" xml:id="ea1"/>According to our survey, 1988

sales of mineral water and soft drinks were much higher than in 1987,

reflecting the growing popularity of these products. Cola drink

manufacturers in particular achieved above-average growth rates.

<anchor corresp="#fa2" xml:id="ea2"/>The higher turnover was largely

due to an increase in the sales volume.

<anchor corresp="#fa3" xml:id="ea3"/>Employment and investment levels also climbed.

<anchor corresp="#fa4" xml:id="ea4"/>Following a two-year transitional period,

the new Foodstuffs Ordinance for Mineral Water came into effect on

April 1, 1988. Specifically, it contains more stringent requirements

regarding quality consistency and purity guarantees.</p>

</div>

<div xml:lang="fr" type="subsection">

<p>

<anchor corresp="#ea1" xml:id="fa1"/>Quant aux eaux minérales

et aux limonades, elles rencontrent toujours plus d'adeptes. En effet,

notre sondage fait ressortir des ventes nettement supérieures

à celles de 1987, pour les boissons à base de cola

notamment. <anchor corresp="#ea2" xml:id="fa2"/>La progression des

chiffres d'affaires résulte en grande partie de l'accroissement

du volume des ventes. <anchor corresp="#ea3" xml:id="fa3"/>L'emploi et

les investissements ont également augmenté.

<anchor corresp="#ea4" xml:id="fa4"/>La nouvelle ordonnance fédérale

sur les denrées alimentaires concernant entre autres les eaux

minérales, entrée en vigueur le 1er avril 1988 après

une période transitoire de deux ans, exige surtout une plus

grande constance dans la qualité et une garantie de la

pureté.</p>

</div>

There is no requirement that the corresp attribute be specified in both English and French texts, since (as noted above) this attribute is defined as representing a mutual association. However, it may simplify processing to do so, and also avoids giving the impression that the English is translating the French, or vice versa. More seriously, this encoding does not make explicit that it is in fact the entire stretch of text between the anchors which is being aligned, not simply the points themselves. If for example one text contained material omitted from the other, this approach would not be appropriate.

<p>

<seg xml:id="e_1">According to our survey, 1988 sales of mineral

water and soft drinks were much higher than in 1987,

reflecting the growing popularity of these products. Cola

drink manufacturers in particular achieved above-average

growth rates.</seg>

<seg xml:id="e_2">The higher turnover was largely due to an

increase in the sales volume.</seg>

<seg xml:id="e_3">Employment and investment levels also climbed.</seg>

<seg xml:id="e_4">Following a two-year transitional period, the new

Foodstuffs Ordinance for Mineral Water came into effect on

April 1, 1988. Specifically, it contains more stringent

requirements regarding quality consistency and purity

guarantees.</seg>

</p>

</div>

<div xml:id="div-f" xml:lang="fr" type="subsection">

<p>

<seg xml:id="f_1">Quant aux eaux minérales et aux limonades,

elles rencontrent toujours plus d'adeptes. En effet, notre

sondage fait ressortir des ventes nettement

supérieures à celles de 1987, pour les

boissons à base de cola notamment.</seg>

<seg xml:id="f_2">La progression des chiffres d'affaires

résulte en grande partie de l'accroissement du volume

des ventes.</seg>

<seg xml:id="f_3">L'emploi et les investissements ont

également augmenté.</seg>

<seg xml:id="f_4">La nouvelle ordonnance fédérale sur

les denrées alimentaires concernant entre autres les

eaux minérales, entrée en vigueur le 1er avril

1988 après une période transitoire de deux

ans, exige surtout une plus grande constance dans la

qualité et une garantie de la pureté.</seg>

</p>

</div>

<linkGrp type="alignment" domains="div-e div-f">

<link targets="#e_1 #f_1"/>

<link targets="#e_2 #f_2"/>

<link targets="#e_3 #f_3"/>

<link targets="#e_4 #f_4"/>

</linkGrp>

<ab xml:id="english1">

<s>According to our survey, 1988 sales of mineral water and soft

drinks were much higher than in 1987, reflecting the growing popularity

of these products.</s>

<s>Cola drink manufacturers in particular achieved above-average

growth rates.</s>

</ab>

</div>

<div xml:id="french" xml:lang="fr" type="subsection">

<ab xml:id="french1">

<s xml:id="fs1">Quant aux eaux minérales et aux limonades, elles

rencontrent toujours plus d'adeptes.</s>

<s xml:id="fs2">En effet, notre sondage fait ressortir des ventes nettement

supérieures à celles de 1987, pour les boissons à

base de cola notamment.</s>

</ab>

</div>

16.4.3 A Three-way AlignmentTEI: A Three-way Alignment¶

The preceding encoding of the alignment of parallel passages from two texts requires that those texts and the alignment all be part of the same document. If the texts are in separate documents, then complete URIs, whether absolute or relative (section 16 Linking, Segmentation, and Alignment), will be required. These external pointers may appear anywhere within the document, but if they are created solely for use in encoding links, they may for convenience be grouped within the linkGrp (or other grouping element that uses them for linking).

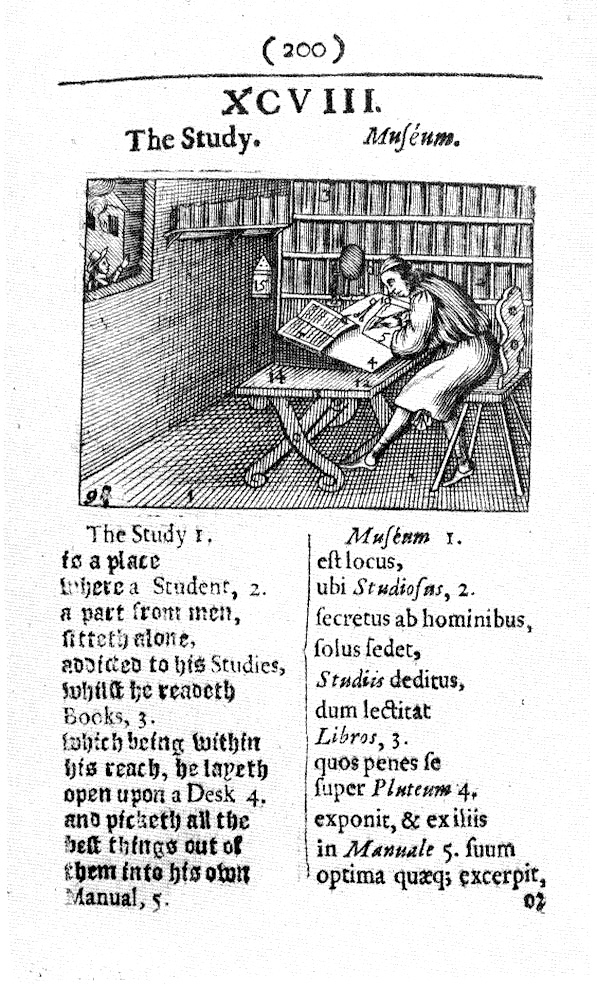

<head>The Study</head>

<p>

<seg xml:id="e9801">The Study</seg>

<seg xml:id="e9802">is a place</seg>

<seg xml:id="e9803">where a Student,</seg>

<seg xml:id="e9804">a part from men,</seg>

<seg xml:id="e9805">sitteth alone,</seg>

<seg xml:id="e9806">addicted to his Studies,</seg>

<seg xml:id="e9807">whilst he readeth</seg>

<seg xml:id="e9808">Books,</seg>

</p>

</div>

<div xml:id="l98" xml:lang="la" type="lesson">

<head>Muséum</head>

<p>

<seg xml:id="l9801">Museum</seg>

<seg xml:id="l9802">est locus</seg>

<seg xml:id="l9803">ubi Studiosus,</seg>

<seg xml:id="l9804">secretus ab hominibus,</seg>

<seg xml:id="l9805">solus sedet,</seg>

<seg xml:id="l9806">Studiis deditus,</seg>

<seg xml:id="l9807">dum lectitat</seg>

<seg xml:id="l9808">Libros,</seg>

</p>

</div>

<image

xlink:href="p1764.png"

width="597" height="897"

id="p981" />

<rect id="p982" x="75" y="75" width="25" height="10"/>

<rect id="p983" x="55" y="42" width="25" height="10"/>

</svg>

- The English and Latin portions are printed in two parallel columns, with corresponding phrases, (represented above by seg elements), more or less next to each other.

- Particular words or phrases are marked as terms in the two languages by a change of rendition: the English text, which otherwise uses black letter type throughout, has the words The Study, a Student, Studies, and Books in a roman font; in the Latin text, which is printed in roman, the corresponding words (Museum, Studiosus, Studiis, and Libros) are all in italic.

- Numbered labels appear within the text portions, linking keywords to each other and to sections of the picture. These labels, which have been left out of the above encoding, are attached to the first, third, and last segments in each language quoted below, and also appear (rather indistinctly) within the picture itself. Thus, the images of the study, the student, and his books are each aligned with the correct term for them in the two languages.

<link targets="#e9801 #l9801 #p981"/>

<link targets="#e9802 #l9802"/>

<link targets="#e9803 #l9803 #p982"/>

<link targets="#e9804 #l9804"/>

<link targets="#e9805 #l9805"/>

<link targets="#e9806 #l9806"/>

<link targets="#e9807 #l9807"/>

<link targets="#e9808 #l9808 #p983"/>

</linkGrp>

This map, of course, only aligns whole segments and image portions, since these are the only parts of our encoding which bear identifiers and can therefore be pointed to. To add to it the alignment between the typographically distinct words mentioned above, new elements must be defined, either within the text itself or externally by using stand off techniques. Encoding these word pairs as term and gloss, although intuitively obvious, requires a non-trivial decision as to whether the Latin text is glossing the English, or vice-versa. Tagging all the marked words as term avoids the difficult decision, but might be thought by some encoders to convey the wrong information about the words in question. Simply tagging them as additional embedded seg elements with identifiers that can be aligned like the others is also a possibility.

<head>The Study</head>

<ab>The Study</ab>

<ab>is a place</ab>

<ab>where a Student,</ab>

</div>

<div xml:id="L98" xml:lang="la" type="lesson">

<head>Muséum</head>

<ab>Museum</ab>

<ab>est locus</ab>

<ab>ubi Studiosus,</ab>

</div>

<link

targets="#element(L98/2) #element(E98/2) #p981"/>

<link targets="#element(L98/3) #element(E98/3)"/>

</linkGrp>

targets="#string-range(xpath1(id('e9806')),16,7) #string-range(xpath1(id('l9806')),0,7)"/>

16.5 SynchronizationTEI: Synchronization¶

In the previous section we discussed two particular kinds of alignment: alignment of parallel texts in different languages; and alignment of texts and portions of an image. In this section we address another specialized form of alignment: synchronization. The need to mark the relative positions of text components with respect to time arises most naturally and frequently in transcribed spoken texts, but it may arise in any text in which quoted speech occurs, or events are described within a time frame. The methods described here are also generalizable for other kinds of alignment (for example, alignment of text elements with respect to space).

16.5.1 Aligning Synchronous EventsTEI: Aligning Synchronous Events¶

- att.global.linking defines a set of attributes for hypertext and other linking,

which are enabled for all elements when the additional tag set for

linking is selected.

synch (synchronous) points to elements that are synchronous with the current element.

This representation uses numbers in brackets to mark the points at which speakers overlap each other. For example, the [1] in A's first speech is to be understood as coinciding with the [1] in B's second speech.57

<u xml:id="u2b" who="#b"> The first time in twenty five years,

we've cooked Christmas <unclear> for a blooming great

load of people.</unclear>

</u>

<u xml:id="u3a" who="#a">So you're

<anchor synch="#t1b" xml:id="t1a"/>

<unclear>

<anchor synch="#t2b" xml:id="t2a"/>

</unclear>

</u>

<u xml:id="u3b" who="#b">

<anchor xml:id="t1b"/>It will be <anchor xml:id="t2b"/>

nice in a way, but, <anchor xml:id="t3b"/>

be strange.<anchor xml:id="t4b"/>

</u>

<u xml:id="u4a" who="#a">

<anchor synch="#t3b" xml:id="t3a"/>Yeah

<anchor synch="#t4b" xml:id="t4a"/>, yeah, cos it, its

<anchor synch="#t5b" xml:id="t5a"/>the

<anchor synch="#t6b" xml:id="t6a"/>

</u>

<u xml:id="u4b" who="#b">

<anchor xml:id="t5b"/>not<anchor xml:id="t6b"/>

</u>

<!-- ... -->

</div>

<linkGrp

xml:id="lg1"

domains="BNC-d1 BNC-d1"

targFunc="speaker.a speaker.b"

type="synchronous_alignment">

<link xml:id="l1" targets="#t1a #t1b"/>

<link xml:id="l2" targets="#t2a #t2b"/>

<link xml:id="l3" targets="#t3a #t3b"/>

<link xml:id="l4" targets="#t4a #t4b"/>

<link xml:id="l5" targets="#t5a #t5b"/>

<link xml:id="l6" targets="#t6a #t6b"/>

</linkGrp>

</back>

<u xml:id="u02" who="#b">No!</u>

</u>

<u who="#b">

<seg xml:id="u-b1"> It will be </seg> nice in a way, but,

<seg synch="#u-a3"> be strange. </seg>

</u>

<u who="#a">

<seg xml:id="u-a3"> Yeah </seg>, yeah, cos it,

its <seg synch="#u-b2"> the </seg>

</u>

<u xml:id="u-b2" who="#b"> not </u>

16.5.2 Placing Synchronous Events in TimeTEI: Placing Synchronous Events in Time¶

- when/ indicates a point in time either relative to other elements in the

same timeline tag, or absolutely.

absolute supplies an absolute value for the time. interval specifies the numeric portion of a time interval unit specifies the unit of time in which the interval value is expressed, if this is not inherited from the parent timeline. since identifies the reference point for determining the time of the current when element, which is obtained by adding the interval to the time of the reference point. - timeline (timeline) provides a set of ordered points in time which can be linked to

elements of a spoken text to create a temporal alignment of that text.

origin designates the origin of the timeline, i.e. the time at which it begins. interval specifies the numeric portion of a time interval unit specifies the unit of time corresponding to the interval value of the timeline or of its constituent points in time.

Each when element indicates a point in time, either directly by means of the absolute attribute, whose value is a string which specifies a particular time, or indirectly by means of the since attribute, which points to another when. If the since is used, then the interval and unit attributes should also be used to indicate the amount of time that has elapsed since the time specified by the element pointed to by the since attribute; the value -1 can be given to indicate that the interval is unknown.

If the when elements are uniformly spaced in time, then the interval and unit values need be given once in the timeline, and not repeated in any of the when elements. If the intervals vary, but the units are all the same, then the unit attribute alone can be given in the timeline element, and the interval attribute given in the when element.

The origin attribute in the timeline element points to a when element which specifies the reference or origin for the timings within the timeline; this must, of course, specify its position in time absolutely.

<when xml:id="w0" absolute="11:30:00"/>

<when xml:id="w1" interval="unknown" since="#w0"/>

<when xml:id="w2" interval="100" since="#w1"/>

<when xml:id="w3" interval="200" since="#w2"/>

<when xml:id="w4" interval="150" since="#w3"/>

<when xml:id="w5" interval="250" since="#w4"/>

<when xml:id="w6" interval="100" since="#w5"/>

</timeline>

type="temporal_specification"

domains="lg1 tl1"

targFunc="synch.points when">

<link targets="#l1 #w1"/>

<link targets="#l2 #w2"/>

<link targets="#l3 #w3"/>

<link targets="#l4 #w4"/>

<link targets="#l5 #w5"/>

<link targets="#l6 #w6"/>

</linkGrp>

type="temporal_specification"

domains="BNC-d1 BNC-d1 tl1"

targFunc="speaker.a speaker.b when">

<link targets="#t1a #t1b #w1"/>

<link targets="#t2a #t2b #w2"/>

<link targets="#t3a #t3b #w3"/>

<link targets="#t4a #t4b #w4"/>

<link targets="#t5a #t5b #w5"/>

<link targets="#t6a #t6b #w6"/>

</linkGrp>

For further discussion of this and related aspects of encoding transcribed speech, refer to chapter 8 Transcriptions of Speech.

16.6 Identical Elements and Virtual CopiesTEI: Identical Elements and Virtual Copies¶

This section introduces the notion of a virtual element, that is, an element which is not explicitly present in a text, but the presence of which an application can infer from the encoding supplied. In this section, we are concerned with virtual elements made by simply cloning existing elements. In the next section (16.7 Aggregation), we discuss virtual elements made by aggregating existing elements.

- att.global.linking defines a set of attributes for hypertext and other linking,

which are enabled for all elements when the additional tag set for

linking is selected.

sameAs points to an element that is the same as the current element. copyOf points to an element of which the current element is a copy.

<q rend="centered italic">

<date xml:id="d840404">April 4th,

1984</date>.</q>

</p>

<p>He sat back. A sense of complete helplessness had

descended upon him. ...</p>

<p>His small but childish handwriting straggled up

and down the page, shedding first its capital letters

and finally even its full stops:

<q rend="italic">

<date>April 4th, 1984</date>.

Last night to the flicks. ... </q>

</p>

1984</date>

Last night to the flicks ...

The sameAs attribute may be used to document the fact that two elements have identical content. It may be regarded as a special kind of link. It should only be attached to an element with identical content to that which it targets, or to one the content of which clearly designates it as a repetition, such as the word repeat or bis in the representation of the chorus of a song, the second time it is to be sung. The relation specified by the sameAs attribute is symmetric: if a chorus is repeated three times and each repetition bears a sameAs attribute indicating the first occurrence of the element concerned, it is implied that each chorus is identical, and there is no need for the first occurrence to specify any of its copies.

An application program should replace whatever is the actual content of an element bearing a copyOf attribute with the content of the element specified by it. If the content of the element specified includes other elements, these will become embedded within the element bearing the attribute. Care must be taken to ensure that the document is valid both before and after this embedding takes place. If, for example, the element bearing a copyOf attribute requires a mandatory sub-component, then this component must be present (though possibly empty), even though it will be replaced by the content of the targetted element.

<speaker>Mikado</speaker>

<l>My <seg xml:id="Mik-l1s">object all sublime</seg>

</l>

<l>I shall <seg xml:id="Mik-l2s">achieve in time</seg>—</l>

<l xml:id="Mik-l3">To let <seg xml:id="l3s">the punishment fit the crime</seg>,</l>

<l xml:id="Mik-l4">

<seg copyOf="#Mik-l3s"/>;</l>

<l xml:id="Mik-l5">And make each pris'ner pent</l>

<l xml:id="Mik-l6">Unwillingly represent</l>

<l xml:id="Mik-l7">A source <seg xml:id="Mik-l7s">of innocent merriment</seg>,</l>

<l xml:id="Mik-l8">

<seg copyOf="#Mik-l7s"/>!</l>

</sp>

<sp>

<speaker>Chorus</speaker>

<l>His <seg copyOf="#Mik-l1s"/>

</l>

<l>He will <seg copyOf="#Mik-l2s"/>

</l>

<l copyOf="#Mik-l3"/>

<l copyOf="#Mik-l4"/>

<l copyOf="#Mik-l5"/>

<l copyOf="#Mik-l6"/>

<l copyOf="#Mik-l7"/>

<l copyOf="#Mik-l8"/>

</sp>

For further examples of the use of this attribute, see 16.8 Alternation and 19.3 Another Tree Notation.

16.7 AggregationTEI: Aggregation¶

Because of the strict hierarchical organization of elements, or for other reasons, it may not always be possible or desirable to include all the parts of a possibly fragmented text segment within a single element. In section 16.1.4 Intermediate Pointers we introduced the notion of an intermediate pointer as a way of pointing to discontinuous segments of this kind. In this section we first describe another way of linking the parts of a discontinuous whole, using a set of linking attributes, which are made available for any tag by following the procedure described at the beginning of this chapter. We then describe how the link element may be used to aggregate such segments, and finally introduce the join element, which is a special-purpose linking element specifically for representing the aggregation of parts, and the joinGrp for grouping join elements.

- att.global.linking defines a set of attributes for hypertext and other linking,

which are enabled for all elements when the additional tag set for

linking is selected.

next points to the next element of a virtual aggregate of which the current element is part. prev (previous) points to the previous element of a virtual aggregate of which the current element is part.

The join element is also a member of the class of att.pointing elements, and so may carry any of the attributes of that class; for the list, see section 16.1 Links.

<s xml:id="qs2">Monsieur Paul, after he has taken equal

parts of goose breast and the finest pork, and

broken a certain number of egg yolks into them,

and ground them <emph>very</emph>, very fine,

cooks all with seasoning for some three hours.</s>

<s xml:id="qs3">

<emph>But</emph>,</s>

</q>

<s xml:id="ps2">she pushed her face nearer, and looked with

ferocious gloating at the pâté

inside me, her eyes like X rays,</s>

<q>

<s xml:id="qs4">he never stops stirring it!</s>

<s xml:id="qs5">Figure to yourself the work of it —</s>

<s xml:id="qs6">stir, stir, never stopping!</s>

</q>

Such a link element must carry a type attribute with a value of join to specify that the link is to be understood as joining its targets into a single aggregate.

- join identifies a possibly fragmented segment of text, by pointing

at the possibly discontiguous elements which compose it.

result specifies the name of an element which this aggregation may be understood to represent. targets specifies the identifiers of the elements or passages to be joined into a virtual element. - joinGrp (join group) groups a collection of join elements and possibly

pointers.

result describes the result of the joins gathered in this collection.

<head>Authors</head>

<item xml:id="a_uf">Figge, Udo </item>

<item xml:id="a_ch">Heibach, Christiane </item>

<item xml:id="a_gh">Heyer, Gerhard </item>

<item xml:id="a_bp">Philipp, Bettina </item>

<item xml:id="a_ms">Samiec, Monika </item>

<item xml:id="a_ss">Schierholz, Stefan </item>

</list>

<join targets="#a_ch #a_bp #a_ss" result="list">

<desc>Authors from Heidelberg</desc>

</join>

The following example shows how join can be used to reconstruct a text cited in fragments presented out of order. The poem being remembered (an unusual translation of a well-known poem by Basho) runs ‘When the old pond / gets a new frog, / it's a new pond.’

<speaker>Hughie</speaker>

<p>How does it go?

<q>

<l xml:id="frog-x1">da-da-da</l>

<l xml:id="frog-l2">gets a new frog</l>

<l>...</l>

</q>

</p>

</sp>

<sp>

<speaker>Louie</speaker>

<p>

<q>

<l xml:id="frog-l1">When the old pond</l>

<l>...</l>

</q>

</p>

</sp>

<sp>

<speaker>Dewey</speaker>

<p>

<q>...

<l xml:id="frog-l3">It's a new pond.</l>

</q>

</p>

<join targets="#frog-l1 #frog-l2 #frog-l3" result="lg" scope="root"/>

</sp>

<join targets="#qs3 #qs4"/>

<join targets="#qs5 #qs6"/>

</joinGrp>

Zui-Gan called out to himself every day, ‘Master.’

Then he answered himself, ‘Yes, sir.’

And then he added, ‘Become sober.’

Again he answered, ‘Yes, sir.’

‘And after that,’ he continued, ‘do not be deceived by others.’

‘Yes, sir; yes, sir,’ he replied.

<body>

<p>

<name xml:id="zuigan">Zui-Gan</name> called out to himself every day,

<q next="#zuiq2" xml:id="zuiq1" who="#zuigan">

<name xml:id="master">Master</name>.</q>

</p>

<p>Then he answered himself,

<q next="#zuiq4" xml:id="zuiq2" who="#zuigan">Yes, sir.</q>

</p>

<p>And then he added,

<q next="#zuiq5" xml:id="zuiq3" who="#master">Become sober.</q>

</p>

<p>Again he answered,

<q next="#zuiq7" xml:id="zuiq4" who="#zuigan">Yes, sir.</q>

</p>

<p>

<q next="#zuiq6" xml:id="zuiq5" who="#master">And after that,</q>

he continued,

<q xml:id="zuiq6" who="#master">do not be deceived by others.</q>

</p>

<p>

<q xml:id="zuiq7" who="#zuigan">Yes, sir; yes, sir,</q>

he replied.</p>

</body>

</text>

<join targets="#zuiq1 #zuiq2 #zuiq4 #zuiq7">

<desc>what Zui-Gan said</desc>

</join>

<join targets="#zuiq3 #zuiq5 #zuiq6">

<desc>what Master said</desc>

</join>

</joinGrp>

Note the use of the desc child element within the two joins making up the q element here. These enable us to document the speakers of the two virtual q elements represented by the join elements; this is necessary because the there is no way of specifying the attributes to be associated with a virtual element, in particular there is no way to specify a who value for them.

<body>

<!-- five div1 elements -->

<div1>

<p>Zui-Gan called out to himself every day, <q>Master.</q>

</p>

<p>Then he answered himself, <q>Yes, sir.</q>

</p>

<p>And then he added, <q>Become sober.</q>

</p>

<p>Again he answered, <q>Yes, sir.</q>

</p>

<p>

<q>And after that,</q> he continued, <q>do not be deceived by others.</q>

</p>

<p>

<q>Yes, sir; yes, sir,</q> he replied.</p>

<ab type="aggregation">

<ptr xml:id="rzuiq1" target="./#xpath1(//div1[6]/p[1]/q[1])"/>

<ptr xml:id="rzuiq2" target="./#xpath1(//div1[6]/p[2]/q[1])"/>

<ptr xml:id="rzuiq3" target="./#xpath1(//div1[6]/p[3]/q[1])"/>

<ptr xml:id="rzuiq4" target="./#xpath1(//div1[6]/p[4]/q[1])"/>

<ptr xml:id="rzuiq5" target="./#xpath1(//div1[6]/p[5]/q[1])"/>

<ptr xml:id="rzuiq6" target="./#xpath1(//div1[6]/p[5]/q[2])"/>

<ptr xml:id="rzuiq7" target="./#xpath1(//div1[6]/p[6]/q[1])"/>

<joinGrp evaluate="one" result="q">

<join targets="#rzuiq1 #rzuiq2 #rzuiq4 #rzuiq7">

<desc>what Zui-Gan said</desc>

</join>

<join targets="#rzuiq3 #rzuiq5 #rzuiq6">

<desc>what Master said</desc>

</join>

</joinGrp>

</ab>

</div1>

</body>

</text>

The extended pointer with identifier rzuiq2, for example, may be read as ‘the first q in the first p, within the sixth div1 element of the current document.’

16.8 AlternationTEI: Alternation¶

This section proposes elements for the representation of alternation. We say that two or more elements are in exclusive alternation if any of those elements could be present in a text, but one and only one of them is; in addition, we say that those elements are mutually exclusive. We say that the elements are in inclusive alternation if at least one (and possibly more) of them is present. The elements that are in alternation may also be called alternants.

The need to mark exclusive alternation arises frequently in text encoding. A common situation is one in which it can be determined that exactly one of several different words appears in a given location, but it cannot be determined which one. One way to mark such an exclusive alternation is to use the linking attribute exclude. Having marked an exclusive alternation, it can sometimes later be determined which of the alternants actually appears in the given location. To preserve the fact that an alternation was posited, one can add the linking attribute select to a tag which hierarchically encompasses the alternants, which points to the one which actually appears. To assign responsibility and degree of certainty to the choice, one can use the certainty tag described in chapter 21 Certainty and Responsibility. Also see that chapter for further discussion of certainty in general.

- att.global.linking defines a set of attributes for hypertext and other linking,

which are enabled for all elements when the additional tag set for

linking is selected.

exclude points to elements that are in exclusive alternation with the current element. select selects one or more alternants; if one alternant is selected, the ambiguity or uncertainty is marked as resolved. If more than one alternant is selected, the degree of ambiguity or uncertainty is marked as reduced by the number of alternants not selected.

- alt/ (alternation) identifies an alternation or a set of choices among elements or passages.

targets specifies the identifiers of the alternative elements or passages. weights If mode is excl, each weight states the probability that the corresponding alternative occurs. If mode is incl each weight states the probability that the corresponding alternative occurs given that at least one of the other alternatives occurs. - altGrp (alternation group) groups a collection of alt elements and possibly pointers.

<u exclude="#we.sun1" xml:id="we.fun1">We had fun at the beach today.</u>

<u exclude="#we.fun1" xml:id="we.sun1">We had sun at the beach today.</u>

</div>

<u exclude="#we.sun2" xml:id="we.fun2">We had fun at the beach

today.</u>